Dr. John B. Arden is a leader in the field of brain-based therapy, which is the integration of neuroscience and psychotherapy. His work gels what is currently known about the brain and its capacities, including neuroplasticity and neurogenesis, with psychotherapy research, mindfulness, nutritional neuroscience and social intelligence.

He has written 15 books on the topic, including Rewire Your Brain, Brain2Brain, The Brain Bible, and The Mind-Brain-Gene, which hit shelves earlier this year. His extensive bibliography includes both research-focused titles targeting clinicians and more practical hands-on self-help books, which tend to appeal to their patients.

Dr. Arden is a US psychologist with over 40 years experience providing psychological services and building mental health programs. Prior to retirement in 2016, he was responsible for leading the largest mental health training program in the US as Kaiser Permanente’s Northern California Regional Director of Training. In this position, he oversaw more than 150 interns and postdoctoral psychology residents in 24 medical centers. He also served as Chief Psychologist at Kaiser Permanente prior to this.

Today, in addition to his writing, Dr. Arden travels all over the world to conduct seminars on brain-based therapy. I caught up with him just as he touched down in Melbourne to speak at the 2019 College of Clinical Psychologists Conference on invitation from the Australian Psychology Society.

Q&A with Dr. John B. Arden

Can you describe a little bit about who you are?

“Well, I worked for Kaiser Permanente in the United States for about 26 years. Kaiser Permanente is the largest provider of multi-dimensional integrated healthcare in the United States, operating in 9 states. We had roughly 3,000 mental health providers. For a big portion of it I was Chief Psychologist at one of the big mental health centres. We had 70 mental health practitioners just in our department. My role was to supervise the psychologists.

Around 2000, I became the Training Director for 24 medical centres. We had about 150 trainees. My focus was trying to figure out how all the elements of healthcare are interrelated and how we could get all the different practitioners talking with one another. So paediatricians, GPs, neurologists, whoever is dealing with your patients. How to get them all communicating to create a more robust way of delivering good healthcare.

As a result, we learned a lot about what the other departments were doing and how we could help one another. Our goal was to try to minimise the overuse of medications as much as possible and really just provide more integrated healthcare. In fact, that’s why I’m here in Australia – to talk about the integration of functional medicine or preventative care, and integrated psychology, because there are so many overlapping dynamics”.

Tell us about your latest book, The Mind-Brain-Gene

“Well, in that book, and certainly what I was trying to do at Kaiser Permanente, is get a better understanding of how healthcare and mental healthcare are interrelated. This is what led me to explore the role the immune system plays in causing dystrophic moods, and how our lifestyle can inadvertently trigger our immune system.

So one of the more exciting areas of science healthcare today I think is epigenetics. In other words, we know that you or I might have particular genes that may not be expressed based on our lifestyle.

Since around the mid 1990s, one thing that we’ve known pretty conclusively is that people who suffer from dysphoric moods – i.e. depression and cognitive fog – are more susceptible to anxiety and stress because of the inappropriate activation of the immune system through chronic inflammation.

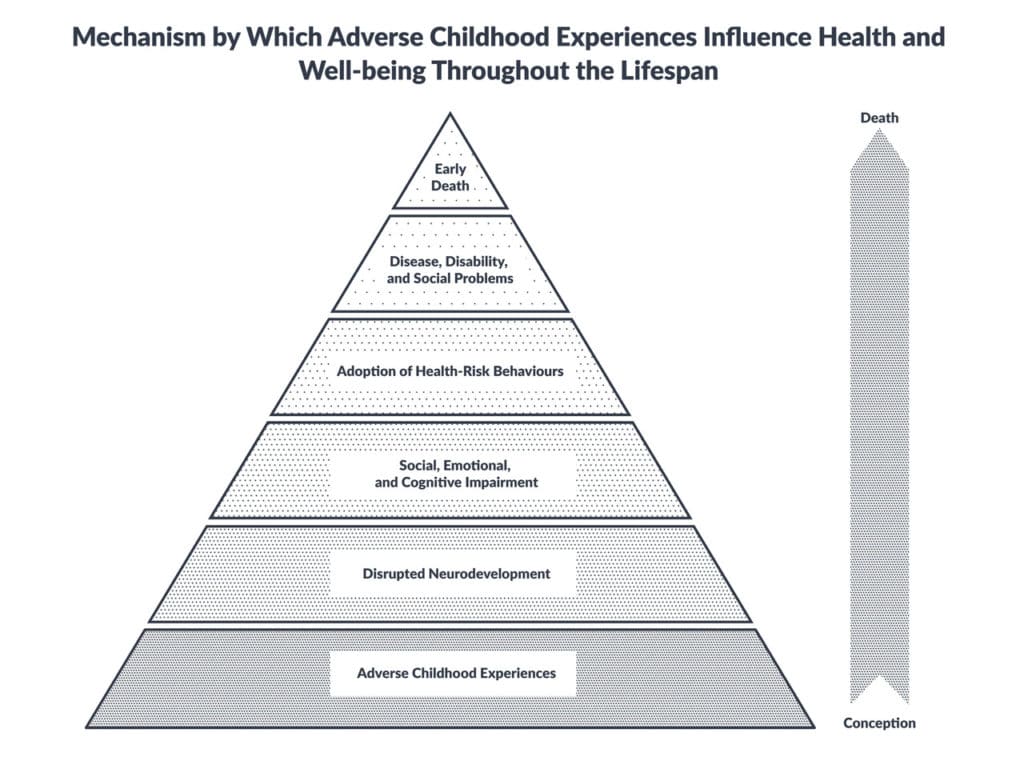

And so, for example, if you experienced a lot of bad things in your childhood, termed “adverse childhood experiences”, then it could be the case that you already started your life out with a chronic inflammatory process going on.

I actually worked in the system that conducted the CDC-Kaiser ACE Study. The study was one of the largest investigations into the correlation between childhood abuse & neglect with later-life health & well-being. It involved data collected from over 17,000 health maintenance organisation members over two years.

Pictured: A replica of The ACE Pyramid published with Kaiser Permenente’s study in the American Journal of Preventive Medicine in 1998. Source: CDC-Kaiser ACE Study

“We know chronic inflammation from trauma and stress often means your brain can’t operate as effectively as it once did, which makes you less stress-tolerant and less resilient compared to other people who haven’t faced the same adverse childhood experiences.

“So, we’re starting to see that earlier in life. Well, actually it’s throughout one’s life. You can degrade the brain’s ability to act like shock absorbers for stress through chronic inflammation in the brain.

“You know, GPs are seeing millions of people all over the world that are complaining about feeling not so good, and they often say, ‘Well geez, it must be all in your head’. Well, to some degree it is because we know this inflammation occurs in the brain too and your brain is in your head.

“We tend to find it easy to connect some inflammatory processes, like IBS, fibromyalgia, arthritis or chronic pain with dysphoric moods and depression, but a lot of people now in the Western world are suffering from chronic inflammation that isn’t directly connected to any of these. This is what I explore in the book.

“We know, for instance, that lifestyle factors lead to things like Diabetes Type 2, but now we’re starting to see that psychological disorders can also be spurred on by chronic inflammation. In fact, many neurologists are now calling Alzheimer’s, Diabetes Type 3.

“So, what we are… and I’m sure you’re focusing on with your information… is how incredibly important it is for mental health professionals and medical professionals to understand they are on the same team and that they need to collaborate far more vigorously”.

Is the book an exploration of the research on the inflammation of the immune system or are there practical elements too?

“Both. The first part of the book talks about the foundations and interactions between all these different systems, and the latter part of the book talks about how these mental health disorders – like anxiety, depression, OCD, PTSD etc – are spurred on by chronic inflammation.

“The reason I talk about these at the end is because at the beginning of the book I talk about how all these aspects are fundamental to understanding how you’re going to help a person get out of that anxiety spiral or that deep-seated depression. Because, while sitting and talking to them about how they feel about their mother or something is important of course, there are far more important interactions to address.

“This is a new century. The 21st century is dramatically different to the 20th. Back then, we were so compartmentalised. Even in mental health, we had all these little theory groups all over the place and hardly anybody talked to anybody else. Now, not only are they talking, but they’re also collaborating with other doctors – GPs, neurologists, endocrinologists, pain specialists and others.”

You’ve written 15 books, including Rewire Your Brain. Which has had the biggest impact and why do you think this is?

“Well, Rewire Your Brain was an effort to bring some of these new developments in neuroscience to the consumer. So it’s more of a self-help book, describing neuroplasticity and neurogenesis and how to rewire your brain in an effort to be very practical.

“A lot of practitioners refer their patients to this book to supplement what they are doing with counselling and psychotherapy. Whereas, Mind-Brain-Gene you could say is less of the mainstream kind of book that you find in a bookstore. It’s more for GPs and psychologists and neurologists who are interested in understanding more deeply what these interactions are about.”

Are there any other books that you’ve written, which you think GPs might find interesting?

“The previous book. It’s called Brain2Brain. In that book, I attempted to do somewhat the same thing, but also offer these little side notes as to how you can actually talk to your patients about psychology. So, instead of talking about the amygdala and the prefrontal cortex and all that, you might say, ‘Your panic button’, ‘Your smoke alarm’, ‘Your top brain’ etc.

“What I’ve been experiencing, and many of my colleagues have as well, is that especially when you travel to places like the Middle East and West Asia where you’re helping with some very, very tragic events. Is that we need to help bring this material down to earth. The same when speaking to Asylum seekers. So Brain2Brain explains how you can talk to people without using a lot of technical terminology.

“The difference between Brain2Brain and Mind-Brain-Gene is that in Mind-Brain-Gene there is a discussion about the immune system and epigenetics.”

Are there any concepts in your books prior to these that you think GPs might find valuable?

“Well, there’s one concept that I think is really useful from one of my books called The Brain Bible. In that book, I describe 5 healthy factors that are critical for longevity and crucial for the stabilisation of mood disorders. These 5 healthy factors are encoded in the mnemonic, SEEDS.

“So if you plant and cultivate seeds over a lifetime, then you’re going to have far better stability, more resiliency, less dysphoric moods, and you’re most probably going to have a brain that functions and is more resistant to dementia.

“So this mnemonic – SEEDS – I think is very, very important. I didn’t come up with these subject areas. I just put them into a mnemonic so clients can remember them and cultivate them on a regular basis.

“I think it’s really critical for GPs to suggest to their clients that if they want to stay healthy, practice SEEDS. S… Sleep. E… Exercise. E… Education. D… Diet. And, S… Social.

“If you get a rotten sleep, you don’t have a good adequate diet, you’re not learning anything, you’re not exercising and you don’t have social support… your telomeres shrink. Your telomeres are the caps on the ends of your chromosomes that protect the chromosomes from damage and are a biomarker for ageing.”

What do you typically present on at seminars?

“I actually do have a section on SEEDS. So the reason I’m here in Melbourne is the Australian Psychological Society has invited me to give a talk on SEEDS and the neuroscience around it. So, psychoendoneuroimmunology. That’s a fancy way of saying the mind-brain-immune system. And the epigenetics around it. But also ‘What is the mind?’ because there is no one thing called ‘the mind’.

“Psychologists have always struggled to define it but now we’re beginning to learn through neuroscience is that there are these mental networks in the brain that seem to be operative. We’re always in these loops between them and they give us particular states of mind.

“So I usually start off my seminars about that, because the people that attend are typically psychologists, but then we quickly get into talking about psychoendoneuroimmunology, the immune system, epigenetics, and how this chronic inflammatory process is being exacerbated by eating a lot of simple carbohydrates and fried foods and not moving much. Of course, there are a lot of other factors too.”

After 40+ years in the field, what is the biggest lesson you’ve learned when it comes to psychology and mental health?

“Ha! I’ve realised how little I know. That’s for certain. And, how much more collaborative science is today. So what’s happening, as I said in the beginning, through the collaboration between integrated medicine and psychology we’re making better ground because we’re treating the whole person. For instance, I’m a psychologist but I swear by SEEDS. I track all my patients by giving them a SEEDS worksheet, which they use to write down how they engage daily in these activities.

They write everything down and when they come back in we go through it. I don’t make them feel terrible if they don’t do something, but of course, my job is to say, ‘Well, how serious are you about really feeling better? What was your diet like? Did you eat 3 balanced meals a day?’ Essentially, a Mediterranean diet. ‘What quality of sleep did you get?’ Without drugs – Benadryl and all that. ‘Did you learn anything new?’ And, ‘Did you have any good social experiences?’”

Do you have any other parting words of wisdom for GPs?

“I really think that the reality is that GPs don’t have a lot of time and I feel for them, I really do. They were my colleagues for many, many years. I ran the largest training program in the US for quite a while and we had a lot of postdocs in behavioural medicine so I’m sympathetic to them. They’re in a compromised position. They want to help, but oftentimes they just provide band-aids because they don’t have the time.

But I think they are in a pivotal position to help reduce the mental health rise by influencing people’s behaviour. Things like SEEDS are a way to treat the whole problem, not just part of it. I believe this would minimise their patient load because patients wouldn’t need to come in as often. That’s what we found [at Kaiser Permanente]… the more we invested in behavioural medicine, the less patients needed to come in. In fact, there are studies that go right back to the mid 1960s that have demonstrated that”.