Clinical Psychologist, Speaker and Author of 8 Books on Autism

Trish lives in Queensland with her husband and three spirited daughters who are all under the age of 10. Along with her husband, two of her daughters are autistic. Last year, Trish attended a conference to learn more about living a full life with autism in the family. It was here she learned a revelationary method for teaching self-regulation skills to adults and children with autism. The method is called ‘energy accounting’.

The energy accounting method

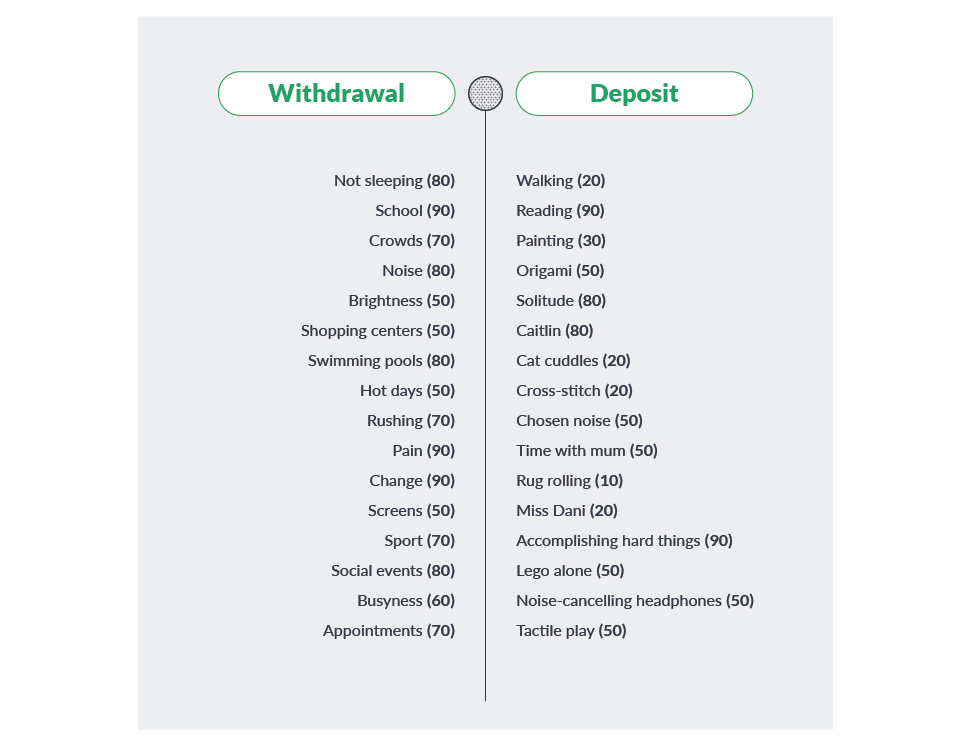

The energy accounting method works by sitting down with the person with autism and creating a long list of things that sap energy from them (withdrawals) and replenish energy in them (deposits). A numerical value is then added to each withdrawal or deposit to give it a weighting.

The idea is that when a withdrawal is made, or numerous withdrawals are made, deposits have to be made too in order to prevent the account running into the negatives, which can trigger a meltdown. After the conference, Trish sat down with her youngest daughter Ellie and they got to work creating their energy accounting list.

Above: An example of an energy accounting list. Withdrawals are things that sap energy and deposits are things that replenish energy, while the numerical values are an indication of by how much.

The conference Trish had attended and learned the energy accounting method from was delivered by Dr. Tony Attwood, a British clinical psychologist who resides in Queensland, Australia. He teaches the method widely after picking up the technique from his colleague, Maja Toudal, an autistic author, speaker and self-advocate from Denmark, who initially created the tool as a way to organise her energy spending while going through school.

Dr. Tony Attwood explains, “I’ve written a book on [energy accounting] and published on depression in Asperger’s and one of the major causes of depression is the amount of energy that’s consumed in coping with everyday life, which builds over time.

“The energy accounting activity can be particularly useful because things can be different in autism and Asperger’s compared to typical people. For example, socialising is more often energising and enjoyable for typical people, but it can be draining and stressful in autism. And these stressors and de-stressors can be wildly different in individuals.”

Meet Dr. Tony Attwood

Dr. Tony Attwood has become one of the world’s leading voices on autism. Since 1992, Tony has been consulting people with autism on a weekly basis. Currently he runs his clinic out of his home where he sees patients a couple of days a week. He also visits people at their homes and schools. When he’s not consulting, Tony is flying all over the world to run conferences on the subject of autism and writing books on his findings.

His book The Complete Guide to Asperger’s Syndrome is the definitive handbook for anyone affected by Asperger’s, whether adult or child. The book has sold over half a million copies and been translated into over 20 languages.

His other books include, Asperger’s Syndrome: A Guide for Parents and Professionals; Exploring Feelings for Young Children with High-Functioning Autism or Aspergers Disorder; From Like to Love for Young People with Asperger’s Syndrome (Autism Spectrum Disorder): Learning How to Express and Enjoy Affection with Family and Friends; Exploring Depression and Beating the Blues: A CBT Self-Help Guide to Understanding and Coping with Depression in Asperger’s Syndrome; and CBT for Children and Adolescents with High-Functioning Autism Spectrum Disorders.

I sat down with Tony to talk more about autism and how GPs and families who have members with autism can better understand and accommodate the condition. The following is the transcription from the interview .

Can you give a bit of a background on yourself for those that might not know of you?

“Well, from my point of view, my interest in autism began in 1971 when I had completed the first year of a psychology degree and met two classically autistic children at a special school. In an instant, I decided that would be my career because I found autism so fascinating at both an emotional and intellectual level. And so, I decided to pursue as much knowledge as I could on autism.

Over the years, I’ve seen our understanding mature from autism viewed as an expression of schizophrenia in childhood to the recognition that it is a neurodevelopmental disorder that includes those who are intellectually very able, often those with Asperger’s Syndrome.”

Those two children with autism you first saw, what was the particular thing that sparked your interest?

“This is at a special school, so first of all, they had no clear dysmorphic or physical characteristics to indicate a problem. So they weren’t cerebral palsy or Downs Syndrome, but they seemed to have great challenges with the social aspects of life and sensory sensitivity. They also seemed to be very, shall we say, anxious and agitated. I just felt, I want to understand life from your perspective to try and help and understand you.”

Do you have advice for GPs in the diagnosis process and how to handle things?

“GPs are the first point of call for a problem. For the young child there can be several pathways to the GP. Eating problems and sensory sensitivity are common issues. Another one for GPs is sleep issues, which are very common in autism.

Communication is another. If the child is delayed in language abilities, or they are having regular meltdowns, which parents can’t alleviate by compassion, affection, distraction and so on.

Also, there is a sign if the person is not as socially engaged as you would expect. They see a room full of toys to play with, not friends to play with. That’s for the young child.

When you’re dealing with a teenager, often by then there can be issues of anxiety. 85% of those with autism, especially Asperger’s, have high levels of anxiety and also depression, often due to a sense of loneliness and low self-esteem.

In teenagers, what can occur is a medical condition is diagnosed and subsequently we recognise autism. For example, eating disorders and gender dysphoria. We’re suggesting that roughly 1 in 4 of those attending an eating disorder or gender dysphoria clinic have signs on the autism spectrum.

For an adult, there is often depression and anxiety, but also relationship issues. So a sign is when a patient comes to a GP and says, ‘Our relationship has problems, what can we do?’ Of course, this is not always the case, but sometimes.”

I know you run a lot of conferences, what is the benefit for those who attend?

“The benefits are in many ways. First of all, you learn information that’s new. But secondly, you acquire affirmation that what you’re doing is okay. It’s very useful to learn, ‘Oh, that’s why that works’. It’s also a benefit to meet and network so you can understand that other people share the same problem. So it sort of reduces the sense of isolation and loneliness.”

Aside from the energy accounting method, are there any other big takeaways people typically get from your conferences?

“Yes, in part, it’s the self-esteem and sense-of-self for the person with Asperger’s because, especially for teenagers, the way I describe it is that their sense-of-self is based on criticism, humiliation and rejection from peers, not compliments and acceptance.

Often my concern is not the person with autism. It’s what their peers do to destroy their self-esteem that contributes to depression. I’m useless, Nobody likes me, I’ll never get a job. A lot of these self-deprecating thoughts actually come from their peer group, not from parents or teachers.

And, over time, they start to believe it.”

Do you have advice for GPs working with people with autism and their families?

“Well, from a GP’s point of view, if you’ve got the time… listen. Listen to either the parent or the person themselves because they need to explain their difficulties.

Another big one is a person with autism can lack a perception of pain and discomfort. That can be that they don’t pick up the signals of you need to go to the toilet. So they can be late in toilet training.

But also, when you’ve got somebody with a medical problem, often there’s a mind-body division and they are unaware. They may have a fracture in their leg, but they just have a bit of a limp that doesn’t seem to be of too much concern. They don’t even flinch, but in fact, when you do an X-ray it’s like, ‘Oh dear, you should be in excruciating pain and yet you’re just carrying on’. So, we do need to tell GPs to be aware of that component.”

What led you to write The Complete Guide to Asperger’s Syndrome?

“Well, I was working for the government, which didn’t work out because I was supportive of parents and families, which was not appreciated by the government when I should have been working to support the minister. There was sort of a disagreement in terms of I was very much for the people with autism and their families, rather than the government department.

So eventually I left. I had a bit of a break before going into clinical practice. I thought, okay, I’ll write a book on autism spectrum disorders but in terms of Asperger’s Syndrome. This was in 1993/’94 when it first came out as a recognised syndrome and so I wrote the seminal book on Asperger’s Syndrome, which has sold over half a million copies.”

What do you credit the book’s success to?

“It was the right book at the right time. It was readable and it was based on clinical experience. I had started, I suppose you could say, one of the world’s first regular clinics for Asperger’s Syndrome back in 1992 and so that became the basis of the book from extensive clinical experience and it was appreciated, not only by professionals, but also by parents.”

What do you consider to be the biggest challenge for a person diagnosed with autism?

“Other people. It’s the ability to read faces, body language, how to interact with other kids from a child’s point of view, and how to make and keep friends. It’s also reading non-verbal communication and having what we call a reciprocal interaction. So their biggest challenge is people. Now, that can be independent of their intellectual abilities or language abilities.”

Can you explain how autism typically affects cognitive abilities and sensory sensitivity?

“Social interaction isn’t the only problem. Another major one is sensory sensitivity. So, certain sounds, aromas, tactile experiences, are painful for the individual. So they have problems with that aspect of life, but also there can be a different way of perceiving, thinking, learning and relating. Now, that means that it’s a different way of learning.

And often, they will have talents in some areas, like knowledge of mathematics or playing the piano, but many have specific difficulties in the area of dyslexia and reading. So we do find that there is a very uneven profile of cognitive abilities and a high propensity for anxiety and emotionality.”

Going back to basics, what is actually happening within the body for this to occur?

“I think, basically, it’s a neurodevelopmental disorder and the brain is wired differently. Part of the difference in wiring is problems with the social reasoning parts of the brain. Other areas may develop talents in terms of problem solving or to sing in perfect pitch, for example. So, I think the best description is a neurodevelopmental rather than a psychiatric disorder.”

Can you explain more about how autism affects social interaction in terms of reading emotions?

“Psychologists use the term theory of mind, which is the ability to read all the social cues that indicate what someone is thinking and feeling. In autism and Asperger Syndrome, that’s not as efficient as it is with someone typically of the same age. So, they have great difficulty understanding the world from the perspective of another person.

From my clinical experience, they struggle not only with the theory of another person’s mind, but also with theory of their own mind. So, when you say, ‘What are you thinking or feeling now?’ Often the answer is ‘I don’t know’ because they have difficulty converting thought and emotion into speech. We call it alexithymia.

So, if a GP or a medical person is asking for that person’s thoughts or feelings, there is a lot going on. They not only find it very difficult to articulate how they are feeling in speech, but they also struggle to reflect on what someone else is thinking and feeling, and struggle to reflect on what they are thinking and feeling themselves.”

What would you consider to be the biggest challenge for a parent when their child is diagnosed?

“I think, first of all, they already know that that child is different and now they have a name for it. But what they need is understanding from other people, such as their teachers, their GP etc. So they need a support network that’s going to help them cope with their child’s social sensory emotional issues. So the problem is usually the system rather than purely the person themselves.”

Do you have any interesting facts about autism that you think GPs might find interesting?

“One of the things that I was looking for but didn’t find before this chat is that there was a research study a while ago which looked at what professions have various levels of children with autism. We know that autism is associated with a father who’s an engineer, but there’s an even higher level with those in information technology. There is also a higher level for those in accountancy, but medicine also has a high level of children with autism.”

Wow. How would you attempt to explain this?

“I think, because one of the things is you have to have a lot of factual information, especially in medicine. You’ve got to have a fantastic retrieval mechanism for knowledge. It’s got to be a scientific way, but also, those with autism and Asperger’s can be very compassionate and caring. And it’s also a very high status profession and often those with Asperger’s want to demonstrate their intelligence and getting a medical degree is one of the best ways of doing it.

So, for example, one of the teenage girls that I’ve seen recently, she’s 13 and desperate to be a heart surgeon. She’s got the intellectual ability and she may well become a heart surgeon, but what she wants to be is valued and needed. And the one profession that has one of the highest values in medicine is heart surgery. So I think this is what is spurring her on.”

Do you have any parting words of wisdom for GPs?

“I think that there is a lot of literature out there and there is the internet. There are many ways of gaining information, but a big thing to remember is that each child and adult is unique. We really need an eclectic approach, rather than a one size fits all approach that says this is a program for all children with autism. It’s a very heterogeneous group.”