A Conversation with Dr. Suzan Bekir

Once upon a time, hay fever sufferers were extremely rare. For instance, when physician John Bostock scoured England attempting to find people suffering from hay fever in the 19th century, he identified a total of 28 people.

By contrast, today the world is experiencing an allergy epidemic. Currently, allergic rhinitis, or hay fever, affects 10-30% of people worldwide. In Australia, 1 in 5 people will suffer from allergic rhinitis at some stage of their life. Skin allergies and food allergies are also on the rise. Today, 1 in 5 Australian preschoolers have eczema, and 1 in 10 have food allergies.

The allergy epidemic

The World Allergy Organisation is certainly aware of the global increase in allergies. While the organisation has noted that food allergies are growing, their prediction is that airway allergies will experience an even greater rise.

This is especially concerning, because airway allergies are often underestimated and trivialised. This is mainly because they appear less serious than other allergies, like food allergies, which can kill people through anaphylaxis.

The airway allergy epidemic is more of a silent killer, “killing us slowly and by stealth,” says Dr. Suzan Bekir, Co-Founder and Clinical Director of Australian Allergy Centre.

Suzan explains, “[Airway allergies] are causing a lot of sleep disorders and making us all really tired with chronic infections. They’re also causing asthma. So, airway allergies may not kill people immediately, but they do kill people slowly. And they do cause chronic ill health slowly.

“The World Allergy Organisation has predicted that these airway allergies and pollen allergies, in particular, will rise. They’ve cited pollution and climate change as the key factors causing this.”

Fortunately, the Australian medical community isn’t taking this news lying down. Because the rise of allergic conditions has created a serious public health issue, the Australasian Society of Clinical Immunology and Allergy (ASCIA) and Allergy & Anaphylaxis Australia (A&AA) developed the National Allergy Strategy in conjunction with other stakeholders.

“The goal of the National Allergy Strategy is to improve the quality of life for Australians suffering from allergies, as well as to develop standards of care.”

This initiative has grown increasingly important, especially when you consider the thunderstorm asthma outbreaks the country experienced just a few short years ago.

Melbourne’s thunderstorm asthma

Dr. Suzan Bekir explains, “We only have to look at unusual events like the thunderstorm asthma events that were killing people in Melbourne a few years ago” as an example of how prevalent allergy problems are becoming.

“There really is an unusual environmental health phenomenon that’s occurring, and we really need to open our eyes to the fact that we need to do something about it.”

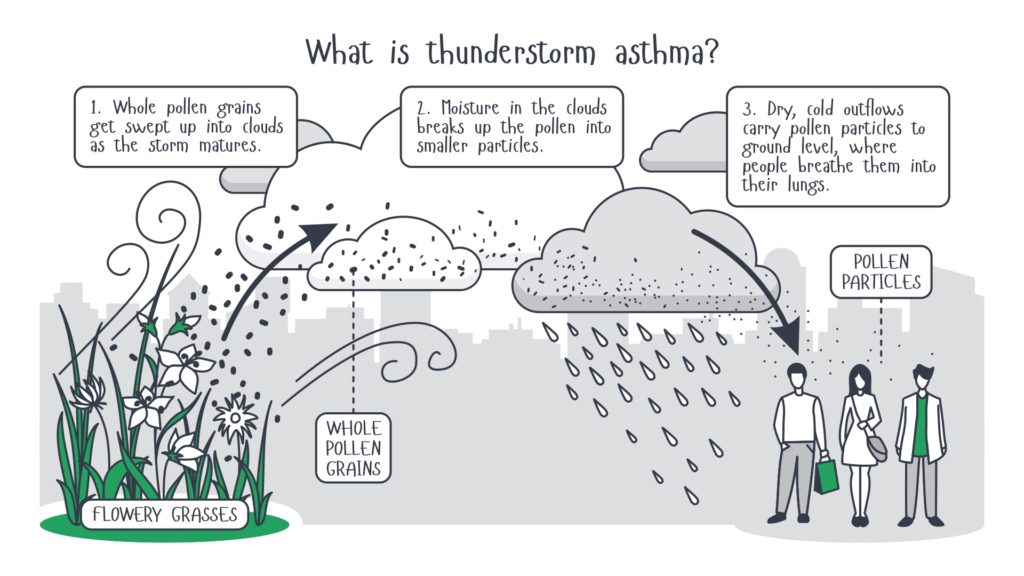

Thunderstorm asthma refers to the onset of an asthma attack during a thunderstorm. This occurs when there’s a high pollen count coupled with heavy thunderstorms.

The reason asthma attacks increase during thunderstorms is because grains of pollen get sucked into storm clouds where they absorb water until they pop — making even smaller grains. These smaller grains of pollen return to the ground and can more easily be breathed in, causing asthma attacks.

In November 2016, a freakish weather event occurred in Melbourne, causing a vast outbreak of thunderstorm asthma. 14,000 people were taken to the hospital, and 10 of them died.

“Most of the people who died didn’t know they had asthma, because they normally just have hay fever. That’s the biggest risk factor,” says Suzan.

“So, they all developed this acute shortness of breath, which caused coughing and wheezing… the emergency departments were flooded, ambulances were flooded, they ran out of Ventolin. I mean, it was an absolute disaster.”

Of course, that leads to the question: how can something like this be prevented in the future? Suzan explains that her centre takes a holistic approach, working with pollen-allergic patients to prevent thunderstorm asthma.

“People really appreciate when you spend some time talking to them about thunderstorm asthma,” Suzan says. “Telling them, ‘This is what thunderstorm asthma is. Have you heard about it? Make sure that if these symptoms occur, you have Ventolin. Here’s a script for it. If there was ever an event that occurred like that, this is what you do.’

“Because, they’ve never heard of it, they wouldn’t know about it otherwise,” she concludes.

Yet as helpful as this kind of patient education is, Australian Allergy Centre does far more than just this.

About Australian Allergy Centre

Australian Allergy Centre offers standardised allergy training to medical teams with the goal of overcoming the allergy epidemic facing the country. This training is primarily for air-related allergies, although it also covers allergy testing and food allergies.

As a start-up, Suzan explains that the organisation’s vision is to have an Australian Allergy Centre in every suburb, ideally through a licensing agreement with existing medical centres. She understands, however, that many clinics might not be looking for that degree of involvement.

Pictured: Dr. Suzan Bekir, Clinical Director, Australian Allergy Centre

Suzan says, “Quite often, [clinics will] just prefer to practice on their own. And so, we provide that support as well, upgrading their skills and tool-set. It’s really all about the tool-set of GPs nationally, and hopefully globally — equipping them with the correct total airway approach.”

To accomplish this objective, Suzan explains that Australian Allergy Centre provides a competency-based education framework. “To achieve that level of competency, we provide almost a 6 month mentorship, which we provide online.

“Then we do a site visit 6 months later where we actually assess the level of competency in the workplace.

“For instance, we would do fire drills with the front desk to see that they know how to manage an emergency that walks through the door. So, it’s very much a team training day. Then we provide ongoing support with products and training.”

“We’ve also developed a number of pathways that utilise nurses more efficiently. So, when children come in with eczema, they automatically have self-care for skin being documented. When a child comes in with asthma, they automatically demonstrate inhaler techniques. Those sort of reminder systems and flags get drilled into the staff.

“We also provide easier ways for them to access skin prick testing or allergy skin prick testing, because that’s what the big wait list is. We’re not here to try and poach patients. A lot of it is just that we investigate, manage and then send the patient back. Obviously, GPs don’t want their patients being stolen from them.

“As for allergy testing, we do skin prick testing for air and food allergies, and contact patch testing for contact allergic dermatitis. There are so many people who are just getting sensitised and allergic to the parabens and the sulphates and the waste product in our self-care products.”

Suzan says that these patients are just told to take one steroid cream after another, and they never have the opportunity to find out what they’re specifically allergic to because they’re not able to access contact patch testing.

She concludes by saying, “We’re about providing allergy testing without people having to wait for a really long time.”

What may surprise GPs about allergies

Knowing our audience, I asked Suzan if there’s anything GPs might be surprised to learn about allergies. She responded by saying, “A thing that maybe GPs don’t know about, would be mouth breathing syndrome in children.

“This condition is much more serious than we used to think, causing delays in development and obviously, sleep problems. It also causes behavioural issues and even grief issues.

“Plus, it affects the way a child’s face looks and the way they smile because when a child’s nose is blocked and they breathe with their mouth open, they hang their tongue quite low.

“The tongue should instead rest on top of the palate behind the front two teeth. In the absence of that, the palate becomes quite high in its arch and the face becomes long and narrow.

“This causes children to develop what we traditionally used to call the adenoid facies, or long-faced syndrome. It can end up being over $8,000 in orthodontics for the parents.

“Allergic rhinitis is significantly implicated in mouth breathing syndrome,” Suzan says. “We all think, ‘It’s just a bit of hay fever’, but it blocks their nose and when it blocks their nose, it causes them to breathe with their mouth open.

“Mouth breathing is an epidemic at the moment, and many GPs don’t know about it. They miss the signs, and unfortunately, missing those particular signs has significant implications on a child’s health, particularly in those critical years.

“I think early intervention at that particular point — unblocking the nose either medically or surgically and then looking after allergic rhinitis in a more holistic, long-term sense — can really improve, or has the potential to affect, the way a child thinks, learns and smiles.”

A common misperception about allergies

Another thing Suzan feels is important for doctors to understand is that allergies are a chronic condition that should be closely monitored.

She explains, “We’re very used to giving an eczema patient steroids or an allergic rhinitis patient a spray, before sending them on their way. But we rarely set review periods. We rarely monitor patients.

“I think defining monitoring periods, a bit like we would with a diabetic, we also need to be doing this for patients with allergies. We really need to see that these chronic medical conditions are going to end up costing us and the community more in the long run, if we don’t pay more attention to them.”

Parting words

When I ask Suzan if she has any parting words for GPs, she responds, “GPs are in a very special position to evaluate a multitude of different treatments. The beauty of general practice is that you can do that. You can offer more than anyone else.

“And, with allergy treatments, we’ve been fed huge amounts of information, primarily from the pharmaceutical industries. Of course, their recommendation is to treat allergies using this steroid cream or that steroid inhaler.

“My message would be that GPs need to take on a much more holistic perspective. There might be emerging evidence that acupuncture is useful. Or, that patients should still use a supporting treatment like essential oils. Or, that saline is the standard and they should first try to rinse their nose. We need to think beyond just what’s being offered to us by drug reps.”

Learn more about Australian Allergy Centre and how the organisation can help your clinic upskill on allergies at their website: www.australianallergycentre.com.au.