A Conversation with Dr. Sarah Myhill

Dr. Sarah Myhill is a British GP who has treated over 10,000 people with Chronic Fatigue Syndrome. Her website, which offers health advice to Myalgic Encephalomyelitis and Chronic Fatigue Syndrome sufferers, has been visited by more than 6 million people. She’s also written five books: Diagnosis and Treatment of Chronic Fatigue Syndrome, Sustainable Medicine, The Infection Game, Prevent and Cure Diabetes, and The PK Cookbook.

The first clue: poisoned farmers

Sarah first gained an interest in Chronic Fatigue Syndrome after working as a GP in rural Wales. During this time many of her patients were local sheep farmers. As part of the process to keep their stock free from flystrike and parasites, the farmers dipped the animals in a solution, which included the poisonous pesticide organophosphate.

To do this, they submerged the animals in the solution by hand for at least 30 seconds. Unfortunately, what the farmers didn’t realise was that, while the solution was the cheapest and most effective, it was also the most poisonous and readily absorbed by the skin.

This meant that many of the farmers became acutely poisoned by organophosphate. Clinically this resulted in fatigue with flu-like symptoms each time they did the dipping. The symptoms would last anywhere from a day to a week before the farmers would recover.

Once the farmers had been sick enough times, however, they never recovered, becoming permanently fatigued.

Sarah explains, they had “aching muscles, foggy brain, they couldn’t think clearly, they couldn’t problem-solve. They couldn’t read a book, because they would lose the plot. Some of them couldn’t even watch television. Then their sleep was disturbed. And they just went downhill with degenerative conditions.

“These farmers in their forties were developing Parkinson’s, heart conditions, even cancers.”

What Sarah discovered was that the organophosphate compounds in the sheep dip were being absorbed by the farmer’s skin and getting into their cells, slowing down the function of the mitochondria.

Sarah explains, “When the mitochondria is going slowly, it accelerates the aging process. And therefore, we get diseases before our time. Neurodegenerative diseases, dementias, cancers and heart diseases.

“In the short term, there’s the chronic fatigue syndrome and inflammation symptoms, which we call myalgic encephalomyelitis, or ME. And in the long-term, we see an acceleration of the aging process.”

When Sarah later saw the same symptoms in those suffering from Chronic Fatigue Syndrome, she wondered if the same thing was happening: the mitochondria had been damaged.

Linking mitochondria to Chronic Fatigue Syndrome

While the connection between Chronic Fatigue Syndrome and mitochondria was at first just a hypothesis, Sarah later strengthened her theory by teaming up with UK biochemist Dr. John McLaren Howard.

Sarah explains, “John developed a mitochondrial function test, and the joy of that test is it gives us an objective measure of how well our mitochondria work.”

“The first scientific paper that John and I produced together with Dr. Norman Booth from Oxford University, found that those patients with the worst fatigue had the worst mitochondrial function, and those patients with the least fatigue had better mitochondrial function.”

Sarah explains, “Broadly speaking, mitochondria often go slow because they don’t have the raw materials to work. If you don’t put oil in your car, or if you don’t have a proper spark plug or the right compression, your car is going to go slow. The same is true for mitochondria.

“The most common problems with the mitochondria are deficiencies in vitamin B3, magnesium, co Q 10, acetyl L carnitine and D-ribose. So, even if you cannot access mitochondrial tests, you can address the nutritional deficiencies very easily.”

Sarah explains that chronic fatigue is a symptom to an underlying problem and that in looking for the causes of that symptom we have to look at how the body generates and expends energy.

How the body expends energy: a car analogy

“A very useful analogy I use all the time to help others understand how energy generation works, is likening the body to a car,” Sarah explains. “There are four important players for energy delivery.

“First, you’ve got to have the right fuel in the tank. There’s no point me putting diesel in my petrol car; it just won’t go. And that has to do with diet and gut function, of course.

“Second, we have the mitochondrial engine. Now, mitochondria are my special area of interest, and this is where I’ve done the most research. It’s something that we all learn at medical school and then we forget it, because it doesn’t appear to have any clinical application.

“But mitochondria and how the body generates energy are involved in almost every pathological process you care to mention. Because if you switch off the energy delivery to the heart, you get heart failure. If you switch off energy delivery to the brain, you get dementia. If you switch off energy delivery to any organ, you get organ failure, whether that’s kidney failure, liver failure, or whatever.

“So, mitochondria are absolutely vital. And every living cell in the whole of nature, from plants to pigs to pineapples; they all have mitochondria. It’s a vital unit of energy generation.

“The third player is the thyroid accelerator pedal. That sets how fast the mitochondria runs.

“And finally, the fourth player is the adrenal gearbox. And what the thyroid accelerator pedal and the adrenal gearbox do, is they closely match energy requirements to energy delivery. Failure in this area is a disaster because, during a severe winter, if we burn up too much energy to try and keep warm, we’re not going to survive the winter.

“Conversely, if I’m walking through the jungle and a sabre-tooth tiger jumps out, I’ve got to run the fastest mile I’ve ever run in my life, or I’ll become breakfast. So, this gearing is very important – to either save our life or to stop us from wasting energy.”

So, if the body is a car with mitochondria being the engine, the thyroid gland being the acceleration pedal, and the adrenal gland being the gearbox, then what causes the mitochondria to go slow?

Sarah speculates that the mitochondria going slow may be connected to gut fermentation.

Gut fermentation: A cause of Chronic Fatigue Syndrome?

While the medical community doesn’t widely accept gut fermentation as a cause of Chronic Fatigue Syndrome, Sarah says the research herself and John McLaren Howard have done may show a connection.

Her theory is that too many sugars and carbohydrates can overwhelm our gut’s ability to digest the food, causing some of these sugars and carbohydrates to ferment instead.

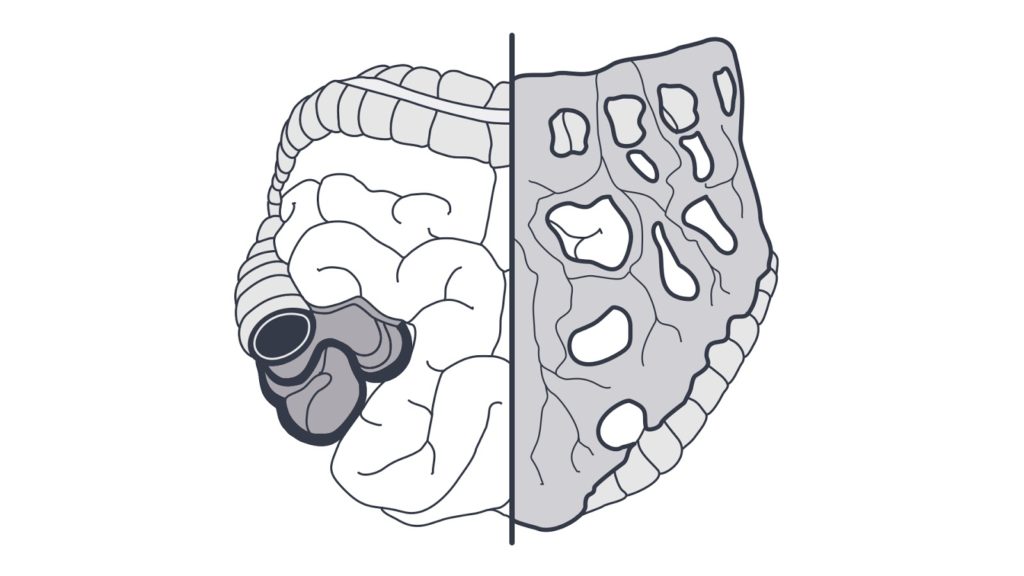

Pictured: An artist’s impression of a healthy gut (left) and a fermented gut (right)

Sarah explains, “When the upper gut starts to ferment, that causes a lot of problems. The first thing is, it will produce products like alcohol, D-lactate, ammonia compounds, hydrogen sulphide and these are harmful.

“The second problem is, you get a buildup in the gut of fermenting microbes, which might be yeast and they might be bacteria.

“A small proportion of those microbes may spill over into the bloodstream. This is called bacterial translocation; it’s a very well-recognised anomaly. If you brush your teeth, some mouth bacteria will immediately get into the bloodstream. It’s the same with the gut.”

Triggering the immune system

Sarah explains that if these fermenting microbes enter the bloodstream they can spread quickly throughout the body and be perceived to be an infection.

“It could be the joints, it could be the muscles, it could be the brain, it could be the kidneys, wherever those microbes end up, they will drive inflammation,” Sarah says.

“Now, when the immune system is activated for no good reason, that is real bad news. Because inflammation gives us a lot of nasty symptoms. It gives us heat, swelling, pain, loss of function.

“The other problem here, is the immune system is our standing army. And guess what? Armies require a lot of energy. So, if the immune system is activated, it takes energy from the body and kicks an immunological hole in the energy bucket. We are wasting energy on useless inflammation and that makes us fatigued.”

Other causes of Chronic Fatigue Syndrome

As well as gut fermentation, Sarah says another common cause of Chronic Fatigue Syndrome is an underactive thyroid. “We need thyroid tremors to be able to burn fat. If we haven’t got that, we can’t burn fat. So, what does the body do? It uses adrenaline instead. And having adrenaline is very uncomfortable. It feels like hypoglycemia. It makes us feel stressed, it stops us from sleeping.

“There’s another factor here as well, which is the subject of another book I’ve written called The Infection Game. We can be carrying infections in our body, at a very low level. And that too, can make us feel ill because we’re getting allergic reactions to dead bacterial, dead viral, and dead yeast antigens.”

The biggest challenge to overcoming Chronic Fatigue Syndrome

In Sarah’s experience, getting patients to change their diet is the biggest hurdle when it comes to treating Chronic Fatigue Syndrome.

She says, “When I see a patient now, I spend 90% of the time persuading them of the importance of following the diet closely, giving them the practical realities.

“Often my consultations turn into cooking lessons. How to make the bread. And how to organise their lives in order to make it happen.

“We can always improve our diet by getting better quality food; organic, grass-fed beef etc, where possible. But, in the beginning, people haven’t got the energy to make the changes. And very often, they haven’t got the money to make the changes either. That’s why the diet needs to be really simple and really cheap.

“I wrote The PK Cookbook, which is full of cheap, simple recipes that anybody can follow.”

More work to be done

Ultimately, more studies need to be done. And with an estimated 30 million people suffering from chronic fatigue syndrome, hopefully that research will receive the funding necessary to prove an outcome soon.

In the interim, if you’re interested in learning more about Dr. Sarah Myhill’s work, you can visit her website. On her site, you’ll find links to her published papers, medical advice, and an online store where her books and health products are available for purchase.