A Moneyball Analogy

This is Part 3 of a 3 part series. Go to Part 1. Go to Part 2.

Recap: In Part 2, we met Dr. Brent James, a trained surgeon and Harvard economist, who was tasked to improve patient outcomes at Intermountain Healthcare. By focusing on quality improvement, Dr. James managed to reduce mortality rates by 2,000 a year, while saving Intermountain’s hospitals hundreds of millions of dollars. In Part 3, we outline the process Dr. James used to achieve this enormous feat.

Today, Dr. James continues to take physicians, nurses and administrative executives through his Advanced Training Program in Clinical Practice Improvement. Over 5,000 healthcare professionals, many in leadership roles, have taken the course, which is designed to help healthcare establishments emulate Dr. James’ results at Intermountain.

Dr. James explains that there are 4 key steps to his course, which are developed from Edward Deming’s principles (discussed in Part 1).

1) Theory of knowledge

2) Understanding things as systems

3) Leading clinical change

4) Understanding variation

If you’re anything like me, you read terms like these and your mind begins to wander. The terms seem abstract and esoteric. That’s because a lot of the foundations of Edward Deming’s principles are abstract and esoteric.

So to provide a bit of stark clarity, I thought that as we unpack these terms we could draw the analogy to Moneyball; the nonfiction book that later became a Hollywood feature starring Brad Pitt and Jonah Hill.

What does Moneyball have to do with healthcare?

If you haven’t seen or read Moneyball, here’s the basic premise of the true story. Billy Beane (Brad Pitt) is the General Manager of Californian baseball team, the Oakland Athletics (Oakland A’s). He’s an ex-Oakland A’s player who quit his professional playing career to be a talent scout for the team. Later he became the General Manager.

In 2001, Beane’s team has an annual budget of $40M and is being forced to compete against teams like the New York Yankees who have budgets up to $114M.

Unable to afford the top players in the league, Beane is convinced his team has no chance of performing well in the upcoming season. That is until he meets Peter Brand (Jonah Hill), a young Yale economics graduate with radical ideas about how to assess baseball player value.

Brand believes that putting the right baseball team together is not about buying players but buying wins. And that wins don’t come from hitting home runs but consistently getting runs, ie. making a run from the batter’s plate to a base without getting out. This way the game is consistently being moved forward.

Brand speculates that when looking to build a team, scouts fall into the trap of undervaluing players for a variety of reasons, such as age, appearance and personality. He also says the scouts measure players on the wrong statistics. They look for superstar player stats, ie. how many home runs have they hit and how fast do they pitch, as opposed to stats that actually win games, ie. does the player get on base and can the player hit.

Brand creates an equation that values players based on their track records of making runs. He uses it to score every player in Major League Baseball. His theory is that the team with the most chance of winning the league is not the one with the most superstar players, but the one with the highest run rate average.

Together, Brand and Beane use the equation to spot and draft extremely undervalued players. Men who have a decent run rate average for a small price tag. This allows them to build a superstar team without a single superstar player.

The result is that the Oakland A’s have a 20 game winning streak; the longest winning streak in baseball history. That same year they manage to win the same number of games as the number one team in the league, the New York Yankees. And they do it by spending one fifth the budget.

Moneyball is a great demonstration of how process trumps individual performance. And how consistently moving the needle forward trumps sporadic big achievements.

Intermountain’s 4 Step Strategy to Simultaneously Improving Patient Outcomes and Reducing Costs

What Brand did to baseball with the Moneyball equation, Dr. Brent James did to Intermountain Healthcare. Focusing on improving the systems at Intermountain’s chain of hospitals, Dr. James and his team reduced mortality rates by 2,000 a year, while simultaneously reducing costs by 13%. This is equivalent to hundreds of millions of dollars over a few short years.

Dr. James says any clinic can replicate the results by following 4 key steps.

Step 1: Theory of knowledge

A theory of knowledge is essentially a hypothesis about how to improve an outcome. Dr. James explains, “First, you need a theory of knowledge about how you figure out what the truth is and how you can consistently apply it.”

If you think about the plot of Moneyball, then the theory of knowledge is the hypothesis put forward by statistician Peter Brand (Jonah Hill) that superstar players don’t win games, making consistent runs does. The theory is that if they can pull together a team of men whose run rate average is higher than any other team, then they can win the league.

At Intermountain, Dr. James’ theory of knowledge was that reducing variation in care would improve patient outcomes, and as a side benefit, reduce costs

Step 2: Understanding things as systems

Understanding things as systems means breaking the thing you want to improve down into individual processes and components. This is so you can collect data on the overall system. Once you have the data, you can then study the system as a whole.

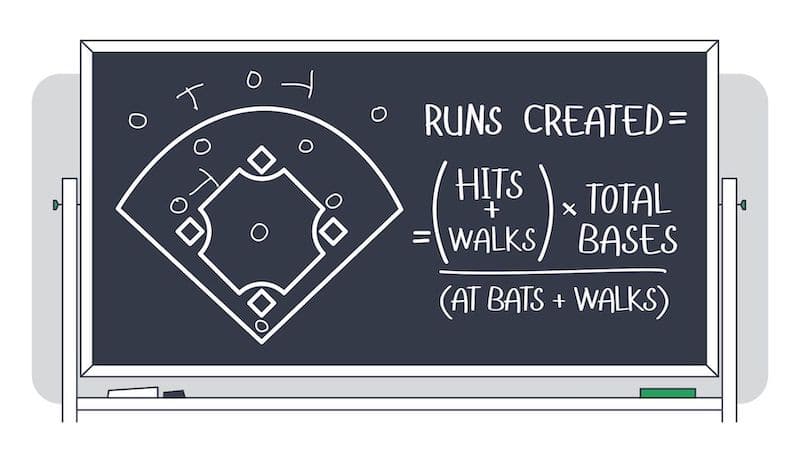

In Moneyball, understanding things as systems is the equation Peter Brand puts together to give every player in Major League Baseball a score based on runs created.

Pictured: The Moneyball equation for measuring player value

At Intermountain, understanding things as systems involved listing every type of inpatient and outpatient care delivered at their hospitals. They counted 1,500 types in total.

Next, they documented everything involved in delivering this care. Everything from bed pans to lab imaging, therapy groups, dosages of drugs etc. They did this by pulling 25,000 line items from a financial record and linking the items to the types of patient care they were involved in.

Dr. James and his team then stacked up all of the types of care in terms of how many patients were affected, the health risk to the patient, and internal variability.

They discovered that 104 types of patient care – 7% of the processes – accounted for 95% of all delivered care. This meant if they could improve those 7% of processes alone then 95% of the hospital care would be improved.

Step 3: Leading clinical change

Leading clinical change means getting buy-in from those involved in making change. Dr. James explains, “The third thing is understanding human psychology in a work setting. You have to show physicians and nurses how the system links to your core ethical and professional commitments.”

In Moneyball, this doesn’t work too well. Billy Beane (Brad Pitt) brings twenty-something year old Peter Brand (Jonah Hill) into a room full of senior scouts. The scouts are pitching ideas on who they feel they should recruit based on instinct and experience.

The scouts act extremely dismissive of Brand’s presence in the room because his theory discounts experience and measures player performance on just one statistic: can the player get on base?

Later, Billy Beane explains to the Head Scout that he needs to get with the times by abandoning instinct and committing to the process because his job is not to get defensive about new ideas and only celebrate gut-wins, but to find the best players with the best tools.

Unfortunately, this doesn’t turn out too well for the Head Scout who quits because he feels threatened.

At Intermountain Healthcare things weren’t so dire. Dr. James champions ‘leading clinical change’ by showing physicians that when you look at the hard facts, you can’t actually be a good physician unless you follow process because variation in care often leads to poorer health outcomes.

Dr. James shares, “Most people come into medicine to serve. Sure, it’s scientifically interesting, but we come in to serve and to help others. And, what we were doing [at Intermountain] was giving physicians a set of tools for doing that dramatically better. It’s a great theory. And then you watch the darn thing work, and it makes you feel really, really good to be a physician.”

So, really this step is about getting those involved understanding that committing to the process is best for all parties because it is directly tied to improving patient outcomes.

Step 4: Understanding variation

Understanding variation is knowing when to step in and override the system. Dr. James shares, “The last area is understanding when variation in your data requires action versus when it’s just random. It’s doctors knowing when they should trust their instincts.”

In Moneyball, this is the moment when Billy Beane trades Carlos Peña, one of their best players, because while on paper he is a great player at getting on base, he is killing team morale.

This is illustrated when Beane enters the locker room after the team has lost their tenth straight game early in the season and Peña is leading the players in a celebration with the stereo blaring, clearly unphased by losing.

Peña’s presence in the team also makes the team’s coach consistently play him first when the theory of knowledge suggests that the team would have better odds with other players starting out first.

Beane recognises that the system is failing with Peña around and trades him for a worse player on paper. Shortly after, the Oakland A’s have the longest winning streak in Major League Baseball history.

At Intermountain Healthcare, this understanding of variation came into play when Dr. James and his team showed physicians when they were better off ignoring instinct and sticking to the process, and when they were better off trusting their instincts.

This came from looking at where the systems typically fell over and empowering physicians to be less reliant on the process in these moments. For instance, when specific types of complications arose or when the physician had access to other data points like family history.

Conclusion

Since the Oakland A’s championed a new way of looking at the game, baseball has forever changed. The year after his team achieved a 20 game winning streak, Billy Beane was offered a $12.5 million contract to be the general manager for the Boston Red Sox. This would have made him the highest-paid general manager in the history of sports.

While Beane turned down the offer, the Red Sox went on to adopt his principles regardless and within two years they won the MLB league for the first time in 86 years. Since then they have won the league four times.

Today, hospitals and medical centres all over the world are doing the same. They look to what Dr. James and his team did at Intermountain so they can radically improve the quality of care delivered in their own institutions.

Dr. James is heralded as one of the most iconic men in the history of qualitative systems improvement. Even the New York Times can’t write a feature article on him that’s less than 8,000 words. His impact on the healthcare industry is simply too epic a tale.

When I ask Dr. James if he has any parting words for health practitioners, he says, “The only thing I’d really tell them is that the evidence is overwhelming. We could dramatically provide much, much better care for our patients if we consistently used these methods. The evidence speaks for itself.”