Q&A with Co-Founder Carlo DiClemente

Carlo DiClemente is the co-creator of the Transtheoretical Model (TTM), often referred to as the Stages of Change Model. He is a clinical psychologist who developed the theory in the 1980s with Jim Prochaska.

Semi-retired today, DiClemente spent much of his early career working at the University of Texas and the University of Houston. He was also Chair of the Department of Psychology at the University of Maryland, Baltimore County, where he has been for the past 25 years.

Today he oversees the University of Maryland’s Tobacco Resource Centre and two other training centres—one for home visitors who work with poor women and children, and another that focuses on HIV.

Prior to becoming a psychologist, Carlo DiClemente was a Roman Catholic priest, who had even been ordained in Rome. He turned to studying psychology after coming to the realisation that what interested him most about people was how their brains worked—how they thought about things and what motivated their decision-making.

DiClemente has spent the majority of his psychology career researching how people change. For instance, he and Prochaska developed the Transtheoretical Model after they began studying why different therapies—therapies with wildly different processes and philosophies—seemed to have similar outcomes.

What DiClemente and Prochaska discovered was that there appeared to be an underlying process that explained how all individuals make decisions.

Working with this knowledge, they mapped out the stages of this process, created a nice diagram, gave it a title, and gathered the clinical proof they needed. Ultimately, the model—the Transtheoretical Model—became so successful that it remains a quintessential part of the training given to all GPs, nurses, aid workers, and caregivers.

I talked to Carlo DiClemente on Skype to learn more about the Transtheoretical Model and its relevance to health practitioners.

Q&A with Carlo DiClemente

What is the Transtheoretical Model and the Stages of Change Model, and what is the difference between the two?

“Well the Transtheoretical Model is an attempt to try and understand the change process. So, what we’re really trying to do is understand how people change. And it really came from some of the early work that Jim Prochaska was doing, trying to see why different therapies all seemed to result in similar outcomes.

“So, we and several other groups compared psychodynamic and behavioural treatments with CBT and others… what you see is that they all do better than waitlist controls, but there’s not much difference in outcome between the two or three different kinds of treatments. That’s a dilemma… that led us to believe that there’s a common underlying process in behaviour change.

“So, Jim was working on creating what he calls the processes of change. Are there some common principles or processes that individuals use in making change happen? What I did was take some of those processes and try to see how smokers changed. And so that’s how we got involved in addiction.

“We tried to understand which processes were important to these people in making change happen. And were they the same processes over different treatments? So, I interviewed people from three different treatment programs and found out that you really have to understand the context of the process.

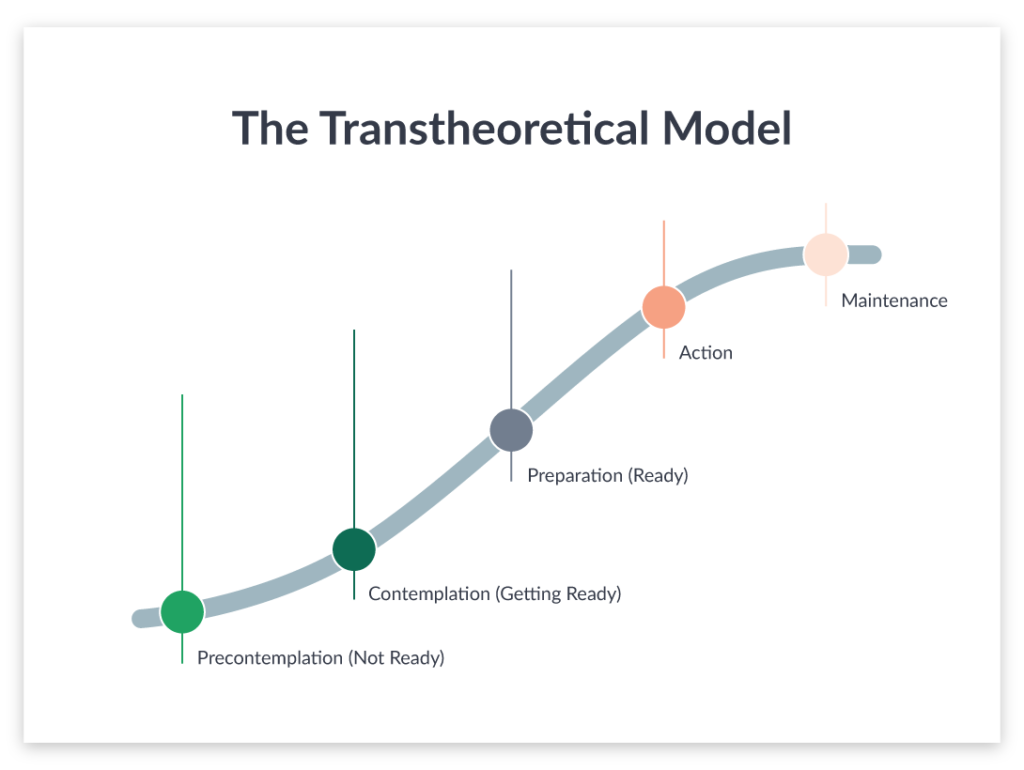

“So, the Stages of Change ended up being the motivational and process dimensions of a change process. How do people go about changing? We knew there were pre-action stages, or things that people needed to do to get to action. And then there are things that people need to do in action, to get through action, and into maintenance.

Above: The Transtheoretical Model developed by Carlo DiClemente and Jim Prochaska

“The stages of change really are this journey that starts from when you’re not interested in changing and ends when you have maintained the change over a long period of time.”

“And what we found is that the stages and the processes interact.

“It’s what you’re doing, what processes you’re using in the early stages versus what processes you’re using in the later stages, that seems to be predictive of people making successful change. And so that’s how we kind of put those two pieces together.

“The Transtheoretical Model has three elements—stages, processes, and what was originally called levels, but now I just talk about them as the context of change… that sometimes the movement through the stages of change and the use of the processes of change can be impacted by the context of someone’s life. So, the context of change is simply the areas where you can find resources and problems that can either facilitate or hinder the change process.

“We began looking at the smoking process and what we realised was that we needed to understand it from the client’s perspective, not the therapy perspective. And so, our first projects were really focused on self-change. How do people quit smoking on their own?

“Jim and I worked on those types of projects, going from studying how they quit on their own, to working on developing interventions that might help them quit–and then kind of evaluating those interventions. We also focused on health behaviour change. So along with smoking came exercise, diet, and other kinds of behaviours… even focusing on anxiety, depression, and some others.”

Can you walk us through the Stages of Change and provide an example of how someone is acting or feeling during each stage?

Precontemplation

“Sure. So, someone in precontemplation is just not interested in making a change. When we measure this, we ask, ‘Are you interested in quitting smoking in the next six months?’ If they weren’t interested in quitting in the next six months, we considered them to be in precontemplation.

“Someone in precontemplation usually believes that they can’t quit, they don’t want to quit, they enjoy it. So, they have lots of reasons and rationales for not wanting to make the change. At least not wanting to make it now.

“Your challenge then is to determine how to get this person to become interested in change. So, that’s a task that someone in precontemplation would have to do, in order to move to the next step.”

Contemplation

“Let’s take contemplation… say this person is only in their 30s and they’re thinking, ‘That’s okay, I can quit later. I don’t need to quit now, this is really helpful’. Then, they have a relative who contracts lung cancer. Or they hear about a heavy smoker who had a heart attack.

“They start thinking, ‘Well, wait a minute. Maybe it is time for me to do this’. Moving into contemplation the person could say, ‘Yeah, I am thinking about doing this in the near term–in the next six months or so’.

“Now you’re in contemplation where the challenge is to do a risk/reward analysis. Okay, there are some risks to smoking, but there’ve got to be some benefits too. So, what are the benefits to quitting? How can I balance for myself the reasons for quitting and the reasons for continuing?

“That’s the decisional balance piece that’s really a key element of contemplation. So, in contemplation, you also see a great deal of ambivalence. You’ll see people say, ‘Well, I know it would be good for my health, but I just don’t know if I can give it up right now’. Or, ‘I know it would be good for my health, but my stresses are too high or too many right now’.

“What gets you out of contemplation is making a decision—a decision to change.”

Preparation

“That transitions you into the preparation stage. In the preparation stage, you’ve made the decision, but the key elements or tasks in this stage are commitment and planning. So, if you’ve made a really good decision, that creates a solid foundation for creating a commitment to follow through. The commitment, or implementation planning, is really important.

“You need to have that to get through the action phase and implement the change. But you also need a plan that’s effective, acceptable, and accessible. If the plan doesn’t have those three elements, it often doesn’t get done or it gets done partially, and there is failure.

“If I get a plan and have the commitment, then I move into implementation.”

Action

“Now I’m making the change, I’m quitting smoking. I set a quit date of Tuesday. I have to implement on Tuesday, putting down the cigarettes, getting rid of the cues, managing the change and subsequent withdrawal effects.

“So, I need to find substitutes. I need to find ways to deal with stress that don’t involve smoking. In the action phase, I implement my plan, and a lot of times the plan doesn’t work.

“What’s critical in action is for people to revise the plan if they run into problems, not quit the change, which is what happens a lot of the time if the plan isn’t working.”

“If somebody goes, ‘Oh wow, this is harder than I thought. I’m having a lot of withdrawal effects, I’m craving cigarettes, I’m really anxious and crabby’, and all of that kind of stuff, most people give up the change, instead of revising the plan.

“Yet, if they were to revise the plan—maybe by saying ‘I need a nicotine replacement’—they’d hopefully continue with the change.

“If the change continues, they’ll develop a new pattern of behaviour. And, in the model we talk about, you need three to six months to create a new pattern. So, you’re in action for three to six months.”

Maintenance

“If you’re successfully in action for three to six months, then you move into maintenance. In the maintenance stage what you’re really doing is consolidating the change. You’re integrating the change into your lifestyle. So, it becomes a new norm for you.

“For instance, in the past year I’ve gotten into maintenance for exercise. So, 2-4 times a week I’m at the gym for an hour or so. I do that kind of religiously and when I don’t—because I’m travelling or something—I have to look for alternatives.

“So, it’s become a part of how I feel good about myself. And that’s maintenance now.”

And people can move back and forth between the stages?

“Yes, some people move into contemplation and go, ‘Nah, I’ve thought it over. I’m not going to do it’. And they go back to precontemplation.

“One of the things that is really unique about the model is that some people can get stuck in different stages. For instance, we followed a group of people we called chronic contemplators.

“For two years, they’d say, ‘Yes, I’m seriously interested in quitting smoking in the next six months’. And they’d do nothing. Another six months would go by, and they’d say the same thing. But they didn’t do anything.

“So, people can think about stuff for long periods of time and be ambivalent about making a change, getting stuck in a certain stage. Mostly in precontemplation and contemplation.

“Also, we know in action and maintenance, not everybody succeeds. So, we have what’s now called relapse. I’m trying to get that name changed because I think it’s blaming, and it shouldn’t be.

“Relapse has often been thought of as a problem with addictions, but it’s not. Relapse is a problem with behaviour change. Sustaining any behaviour change is very difficult.”

“When we studied the people we classified as relapsers, they weren’t a group that was very homogeneous. Some of them looked more like people in precontemplation, some of them looked like people in contemplation, and some of them looked like people who were getting ready to make another attempt to change.

“We realised that relapse triggers this recycling process where people go back through the stages in order to get the process right. So, basically, change is a learning process. Relapse is like falling off a bike. Now you have to get back on and learn how to ride it, so you don’t fall off again.

“What I now believe is that you have to complete each of the tasks of the stages adequately to support moving through that process. To use myself as an example, I was a smoker when I started doing this research, so I know my research has helped at least one person because I quit.

“But I made what I would call half-hearted attempts to quit. In fact, in smoking research, we say you have to quit for at least 24-48 hours, and it has to be because you want to quit, not because you’re in a hospital and can’t smoke. Otherwise, it doesn’t qualify as a quit attempt, because lots of people stop for an hour or two before picking up a cigarette again.

“It’s learning… the model is a learning model. It’s learning how to do this process well, so you’re successful in terms of maintaining a desired change.”

How can people help those who relapse feel like they are moving upward in the spiral?

“I think we should focus on success. So, what parts of this process did you do well? Focusing on that, focusing on how long they were able to stay off this time. Focusing on what it would take to make this more successful.

“Matthew Syed has a book called Black Box Thinking. It tries to get people to think like the airline industry, which is one of the safest industries we have. That’s because they do such wonderful work examining their crashes… to make sure something similar never happens again.

“We need more black box thinking around relapse—to figure out what’s going on and how we should fix it. But look at the whole process, not just the action phase. Because then people might, say, ‘You’re too stressed, let me help you with your stress’.

“Well, if their decision wasn’t strong enough, helping someone with their stress isn’t going to fix the issue. So, I think focusing on the positive and helping them to explore the process is valuable.”

From all your studies, what’s the biggest learning you’ve come across about the human condition?

“I think people have an incredible capacity for not changing. Once people are comfortable with a particular behaviour pattern, they don’t like to change. So, I think the strength of people in precontemplation continues to amaze me.

“I mean, look at some of the people who are addicted. They have an opiate overdose, an EMT gives them Naloxone, they wake up and they go, ‘Okay, I’m good’. Then, they go off. Later that same day, [EMTs] get called out again to rescue this person from another overdose.

“So, precontemplation is a well-established pattern of behaviour. And addictive people don’t have access to self-regulation and all the other kinds of things that would help them come out of precontemplation.

“The other big learning is that people can change, and that change can happen in a brief period of time. But I also know that people with severe use disorders, people with really seriously compromised self-regulation, need a lot of support and a lot of time to make that change.

“The thing about this model is that it’s a heuristic. I think the reason it’s been so successful is because people find it innately understandable. It helps people understand there’s a journey involved.

“I think the model’s been able to help providers realise that they don’t have to make the change. Instead, they have to empower others, not try to predict or prescribe the change.”

What advice do you have for support workers, doctors, psychologists, etc when trying to empower people to change?

“Motivational interviewing can be very effective. It involves listening to people and reflecting, rather than trying to get them to change… with this method, a lot of times people will talk themselves into change.

“And, if they have the resources and self-regulation to do it, they can do it on their own. But once they talk themselves into change, you must give them the support they need to really make that change.”

What about someone who relapses? Is there a way to be helpful, because oftentimes there is a lot of guilt and shame?

“That’s why I want to change the word relapse, because it seems to be blaming. Again, I think the solution is to think about this as a learning process. Everyone can learn how to change their behaviour. It may take time, it may take energy, it takes support. But people can do it if you give them a chance and support them through this process.”

Is there a better name than ‘relapse’?

“I think it’s better to talk about a reoccurrence. That’s what we do with diabetes. I mean, insulin shock doesn’t get called a relapse. Instead, it’s considered a reoccurrence.

“Ultimately what I’ve been thinking is we have a very difficult time deciding what a relapse is. Now, if you’re in AA, any touch of alcohol is a relapse. I don’t think that’s particularly helpful.

“I think that slips are important, because slips tell you that your plan isn’t working in the action stage… my view is that when you quit the change, that’s when you’ve relapsed.”

Do you have any parting words for health practitioners?

“Just that you don’t want to label something a relapse until you understand where the person is in the [change process]. If somebody’s smoked five cigarettes, for example, deal with that as a problem in the action plan, rather than a relapse at the beginning. So, don’t be too quick to label something as a relapse. Instead, focus on the progress.

“I also think doctors can be really helpful if they ask questions and listen to the answers.

“I think sometimes [doctors] are afraid to ask open-ended questions, because the patients will start going on and on… but I think it’s really important for them to ask a couple of probing questions, rather than give a lot of advice. Probing questions will help you target the kind of advice that you need to give.