A Conversation with Michael Pugh

When Michael Pugh (pictured above) first came to Colorado to run Parkview Health System in 1984, he was told the story of a physician (let’s call him Dr Artie to conceal his identity) who had worked at the hospital prior to Pugh’s arrival. Dr Artie had been a surgeon in the military in Korea before joining the hospital as a general surgeon. He had a huge following among patients and many considered him the sole reason the hospital was able to stay open.

Dr Artie tended to as many as 60-70 patients in the hospital at any one time and patients loved him. He had a track record of good surgical outcomes and a huge following of loyal patients. From the outside, he appeared to be the perfect surgeon. However, this was only because there wasn’t an appendix, gallbladder or uterus that Dr Artie didn’t think he should take out. His dirty little secret was that he was operating on healthy people as much as unhealthy people.

It wasn’t until late in his career that he was finally caught by an anaesthesiologist at the hospital. Dr Artie would frequently drop by the laboratory to talk to a pathologist who kept a big jar of gallstones that had been removed during surgeries. He would distract the pathologist and sneak gallstones out of the jar and plant them in the surgical pan when he removed a healthy gallbladder. The anaesthesiologist caught him in the act. Shortly after, he was run out of town.

“I think you get the moral of the story,” Pugh says. “Sometimes patient satisfaction, and what’s perceived as a good patient experience in the eyes of the patient, doesn’t mean good health outcomes.”

Michael Pugh is a veteran when it comes to quality improvement in healthcare. He has over thirty years of CEO experience in hospitals and managed care organisations and is the Vice Chair of the Leadership Faculty at the Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI). He is an Adjunct Professor at the University of Colorado Denver Business School and runs his own consulting company, MdP Associates.

I sat down with Pugh to discuss more about his views on what a genuinely good patient experience looks like when a story like Dr Artie’s turns everything on its head. After all, if you asked Dr Artie’s patients at the time, most would likely rate their patient experience as ‘exceptional’—they felt great afterwards.

What does a good patient experience look like?

The most haunting aspect to Dr Artie’s story is that it shows just how different a good experience can be in the eyes of a patient compared to the eyes of a healthcare worker. And while the story is a tale of the worst-case scenario, Pugh says, “[A healthcare worker] has to remember that most often a good or bad patient experience is determined through the patient’s eyes.”

“The flip side to [Dr Artie’s] story is that you can get a great clinical outcome—you can operate on someone’s knee and fix their torn ACL, and get a great result—but if the patient doesn’t like you because you’re late, and you’re rude, and they get pain after surgery that you never told them they were going to get, then that’s a bad result,” Pugh says.

“I believe a genuinely good patient experience is achieved when the clinical results align with what matters to that patient.”

Pugh says, “An example is someone who is elderly. Let’s say they have heart disease and are really struggling to get better. Delivering a good patient experience comes down to finding out what really matters to them. Maybe it’s to be able to see their grandson born four months from now. So you do everything you can to help make sure they’re still around four months from now. It may not be all the other stuff.”

This begs the question, how can you actually measure a good patient experience if the conditions are unique to each patient?

An improved measurement of patient experience

“We have to remember that patient satisfaction and patient experience are different things,” Pugh explains. “Years ago, there were some research protocols around patient experience and satisfaction called Short Form 36. It was a Rand Corporation questionnaire that asked patient’s after 60 days, ‘Are you better than you were before?’ These types of surveys are much more reliable than asking a patient about their experience at discharge.”

Pugh’s point is that surveying patients the moment they are discharged produces a false metric on whether the patient’s experience was good or bad because such surveys tend to measure patient satisfaction around bedside manner and other services provided by the hospital—the food, amenities, staff friendliness etc—rather than the actual long-term health outcomes.

Pugh says, “One of the big issues in the United States, not so much in other countries, is that patients are oversold on total needs. So they have a lot of knee pain and somebody says, ‘We can replace that and get rid of your pain.’ And they go, ‘Great!’ Then after the surgery, the patient returns for a follow-up appointment and says, ‘Well, I’m ready to go skiing again.’ And the surgeon says, ‘No, you can’t ski with an artificial knee.’”

Without having an initial conversation about what the patient is hoping a treatment will do prior to beginning treatment can lead to false expectations. And these false expectations are often not uncovered until weeks or months after discharge.

Pugh explains, “You really have to have the patient document what they would like to do post-treatment. You have to have a conversation about what their expectations are and see if there is a mismatch between what they want and what they are likely to get.”

Learning from the little guys

Beyond setting expectations, Pugh suggests those looking to improve patient satisfaction can learn a lot from “smaller, primarily rural hospitals—those under 100 beds.”

“The smaller hospitals knock the socks off larger hospitals when you look at patient satisfaction scores.”

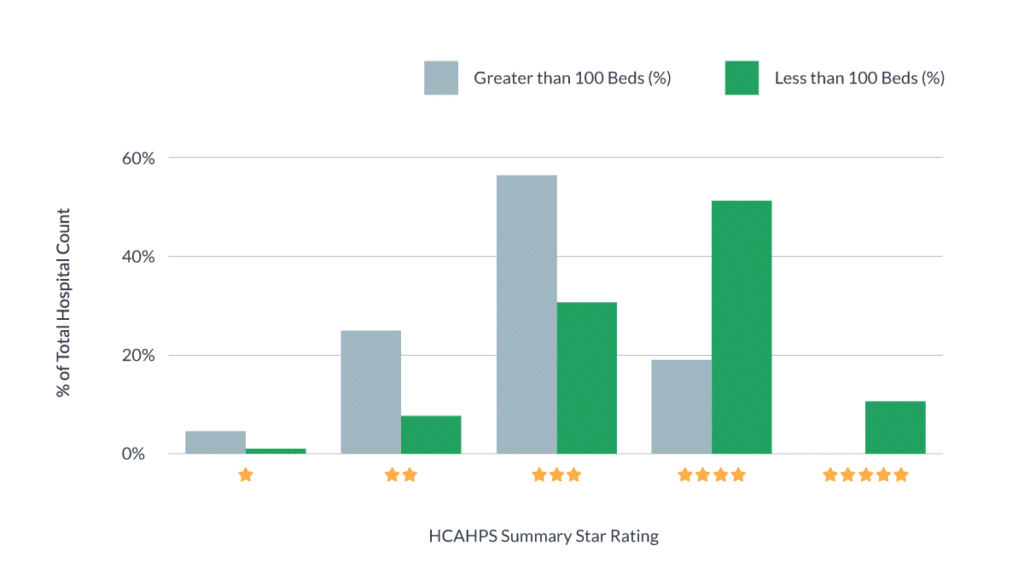

“I was just looking at the data,” Pugh shares. “Sixty-percent of small hospitals [under 100 beds] score four or five out of five for patient satisfaction. Whereas, if you look at larger hospitals [over 100 beds], it’s more like 20% of hospitals scoring four or five.”

Above: HCAPS data for Q4 2019 taken from over 3,000 US hospitals

Pugh says he believes this may come down to the number of human interactions a patient is likely to have in a smaller hospital.

“If you think about going to a large, busy, urban facility, you can’t find a place to park, you can’t find your way in, and when you finally get in there are people everywhere and you feel like nothing more than a number. It’s sort of the difference between staying at the big Marriott downtown or staying at a wonderful little boutique hotel,” Pugh says.

Knowing how patients feel about their health several months after treatment at a small hospital compared to a big hospital is a little more difficult to uncover because so few facilities actually measure patient satisfaction this way. This itself is cause for concern.

Fears for the future of the patient experience

Looking forward, Pugh says he has concerns about the future of the patient experience, mainly due to the spread of misinformation, which is causing distrust among patients.

Pugh says, “I’m worried about the power of social media negatively impacting the belief in science. Anti-vaccination groups, for instance, are getting bigger without any scientific background. And we have a President that suggests that maybe we should drink bleach to kill COVID. These types of things are spinning us in a direction where patients have expectations [about the healthcare industry] that have to be unbundled.

“I used to believe that patients would be able to get on the internet and become much more empowered. Instead, it is turning out that social media is making it much more difficult for folks to understand health care.

“The second thing I’m worried about is all this talk about us having an over-utilisation problem within the emergency departments in the United States. Then COVID happens and suddenly all the patients disappear because they are afraid they are going to catch something if they come to the hospital.”

“[In one month after COVID started] the number of patients who had strokes and showed up to California’s Providence Healthcare System, fell nearly in half.”

“This has really worried me,” Pugh says.

“It’s going to be some time before we find out what really happened with chronic disease and heart attacks and strokes because of COVID. I think we’re going to have to work really hard to rebuild trust with patients and make them willing to come in and be treated at hospitals because of all this misinformation. It makes it hard to predict the future of the patient experience.”