A Conversation with Dr Nick Carr

For 25 years, Dr Nick Carr from St Kilda Medical Group has been teaching GPs how not to write prescriptions for drug seekers. He runs a workshop for all GP Registrars in Victoria, teaching them how to best speak to doctor shoppers to limit prescription drug misuse. He is also regularly featured on radio stations, like ABC and RRR, and TV segments, like Insight on SBS.

I knocked on the door of Dr Nick’s home to do the interview. “Welcome!” He said with a friendly grin. I had caught him on his day off and he was dressed in a casual sweater and jeans. “Meet Sam and Rosie” he said as two placid poodle cross border collies came pattering down the wooden hallway to sniff my boots. “Head down the hall” he said holding the door for me. I walked down the hall into an open living room that was filled with natural light and overlooked a lush garden.

Dr Nick got to work putting on a pot of green tea while I set my computer up. When the tea was poured he sat on the sofa opposite me. Rosie sat beside me and dropped her ball. Sam jumped up on the couch and lay next to Nick. Conscious of time, I dived in.

What were the steps that led you to get involved with GPs prescribing addictive drugs to patients they don’t know?

“Well, I originally worked in Camden Town in London and saw an awful lot of people who were using drugs and misusing prescription drugs. And then I came to Melbourne and ended up on Grey Street, St Kilda, and saw an even larger group of people who were wanting and needing a prescription for uses that were non-therapeutic.

“I was astonished by the numbers of people who were looking for prescription medication and misusing these things. The thing that really got me involved was the fact that GPs didn’t really know how to manage this problem at all. I had been poorly taught and needed to rethink the issue because no one else had taught me how to deal with the issue properly.”

How bad is the problem?

“We’re killing people all over the place with prescription medication. We have more people die from prescription drugs than we do from heroin. And more people are killed with prescription medications than die in our roads tolls. That’s an appalling figure.”

What role do doctors play in the epidemic of prescription drug addicts?

“If we could stop the easy supply of these things then we would immediately reduce the number of people dying, or who have a life dominated by addiction. That’s why I firmly believe doctors need to take much more responsibility in initiating addictive drugs.

“For instance, my 16-year-old son got his wisdom teeth taken out and he came out with a packet of 20 endone. No one said to him, these things are highly addictive, use them sparingly, don’t take any more than this one packet. There was no warning about driving or anything like that.

“What often happens is people take those 20 endone and they quite like it. They get a bit of a buzz and they go back to the doctor and say, ‘My wisdom teeth still hurt’. They get some more and within two or three weeks they are an addict. We have to take responsibility and stop doing that. We have to stop saying to people who are anxious, ‘Here take some valium, you’ll feel better’, because they will feel better. It works amazingly and a month later they are a valium addict.”

What is a doctor shopper? And how can a GP spot one?

“A doctor shopper is someone who is turning up to a doctor who doesn’t know them and asking for addictive prescription drugs. Today, the most common way for a doctor shopper to operate is to walk in and say, ‘I need a top up of my medication’, and then they tell you the name of the drug.

“The other thing people do is walk in with a symptom — pain, anxiety, stress, insomnia — that sort of thing. A symptom that suggests the need for a target drug. If that person knows the name of the drug they are after then again they are likely to be a doctor shopper.

“There are other indicators too. Doctor shoppers are known for turning up without appointments, often later in the day because they’ve been bombed out in the morning.

“There is a funny clue. [Doctor shoppers] often have medicare numbers with a high terminal digit because the last number on your medicare card changes every time you renew your card

“Doctor shoppers tend to live rather chaotic lives and lose their medicare card a lot. So, if I see a 24 year old whose medicare card ends in an eight or a nine, that is sometimes a clue they could be a doctor shopper.”

What should doctors do when a doctor shopper comes into their practice?

“What I believe we need to do with doctor shoppers is never prescribe them with any drug of addiction. Full stop. It’s just not safe. There is plenty of evidence that we kill people doing that. And there is essentially zero evidence that we ever harm someone by not giving them drugs of addiction when we’ve never met them before.”

How can doctors say ‘no’?

“When I see a doctor shopper my heart rate still goes up because I know it can be difficult and I’m not sure how they are going to react. It is regularly rated as the most stressful consultation junior GPs have to manage. The first step I always teach Registrars is to seek the ‘doctor shopping request’, which is the name of the drug. And then as soon as you hear it you simply say, ‘I don’t prescribe valium, serepax and endone’, and then stop — which nobody can ever do the first time.

“The response when you say this to people is really fascinating. Roughly a third of all people say, ‘Oh, that is really good, Doc. Well done. More doctors should do that’. Which sounds odd but it’s not odd when you understand the agenda because they know you shouldn’t prescribe this stuff.

“Some of them say, ‘Well what am I supposed to do doc? You’re an f***’ and all of that sort of stuff. And some of them get threatening. In that situation I just name it for what it is – a direct threat. Sometimes when they’re threatening I teach people to say, ‘There is no point in shouting and swearing at me. I don’t prescribe these medications to anyone’. This depersonalising seems to take the heat out of it.

“And the other thing worth saying is that to do it well it needs to be a whole practice approach. It doesn’t work if one doctor in the practice says no but everyone else is dishing it out. We have a sign on our front door that is very carefully worded. It says, ‘The doctors in this practice prefer not to prescribe drugs of addiction, such as…’ and then lists a few of them. It doesn’t say, we never. It just says, we prefer not to. About twice a week someone walks up, looks at the sign and walks away.”

How can doctors help doctor shoppers?

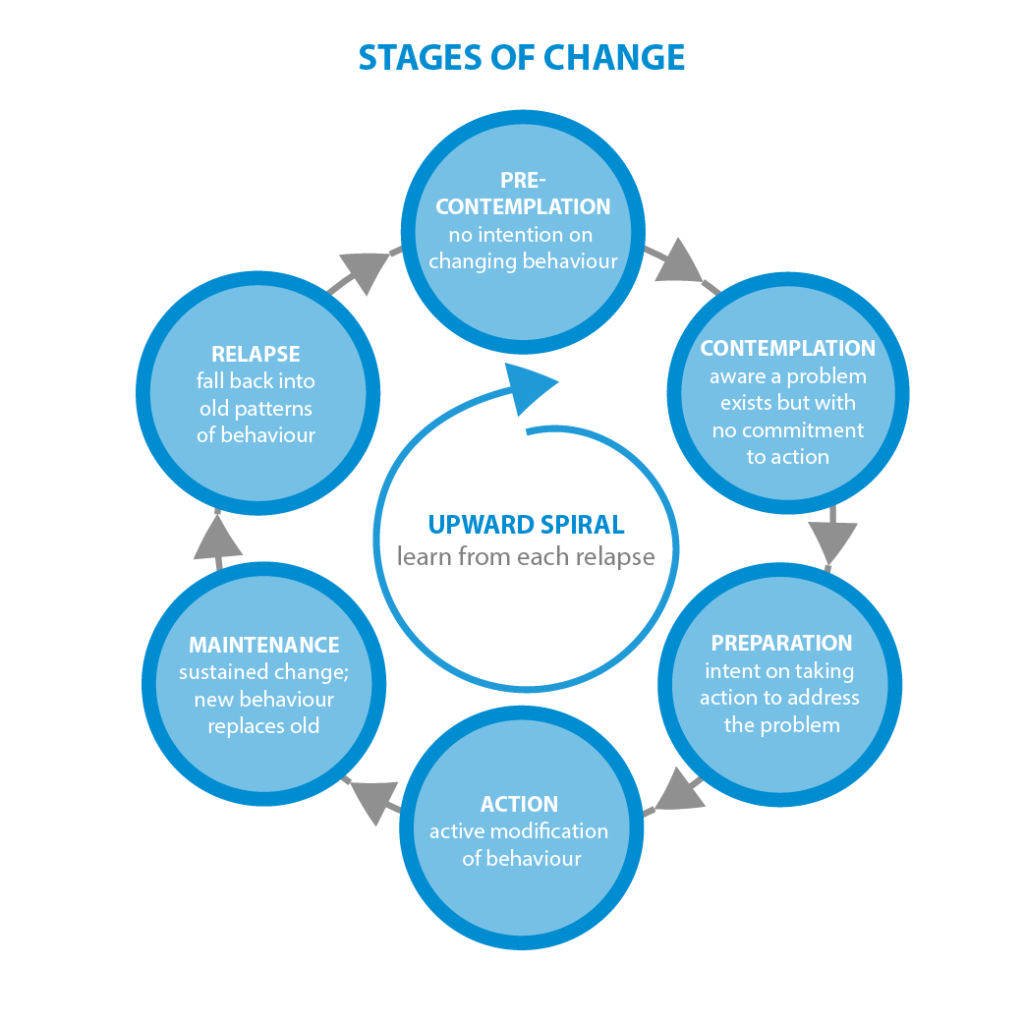

“This is an absolutely crucial point. There is a stages of change model, also known as the Prochaska & DiClemente model, where these people are what we call ‘pre-contemplators’. We talk about pre-contemplators, contemplators, ready for action, action and remission or relapse.

Read our interview: The Stages of Change Model: A Conversation with Carlo DiClemente

“Pre-contemplators are at the top of the chain. They are people who are not trying to change. They just want their drugs. They’re equivalent to the drunk at the bar who wants another whisky. Talking to that person about the harms of alcohol and whether or not he should contact an alcohol counsellor is not going to get us anywhere because he just wants another drink.

“Pre-contemplators are really really hard to help, but what the research shows is one way that doctors can help them is by denying them access to their drug of choice

“The idea is to make them uncomfortable so they think, ‘Shit, this is not good. I haven’t gotten any and I’m hanging out and I don’t like it. Maybe I’ve got a problem’.

“The second way refusing them access helps is that it makes you a reliable doctor they can come back to. 100% of doctor shoppers said they would not go to a prescribing doctor for medical help, but they will come back to someone who refused to prescribe. I’ve always estimated that 3 to 5% of them will come back sometime in the next 6-months and the opening line is always the same. ‘I remember you wouldn’t prescribe. Now I want help with Hep C or whatever’.

“The third way we doctors can help is by not increasing supply of the drug as this is also proven to reduce the risk of harm”

How does a ‘Real Time Prescription Monitoring Service’ help doctors say ‘no’?

“The coroner has been saying for years and years that we need an electronic system that helps doctors say no when they’ve got a person in front of them saying, ‘I’ve just come here from Adelaide and I’ve left my endone and such and such behind’. They need a way to find out whether that person has had [the drug] before or had it recently. And that’s what’s called a ‘real time prescription monitoring service’.

“I’ve spoken to the pharmacist who runs the DORA system in Tasmania and I’ve looked at the data and it has been very successful at reducing the harms that come from prescription medication.

“The DORA system has taken Tasmania from the highest death rate per population for prescription drug overdose to the lowest

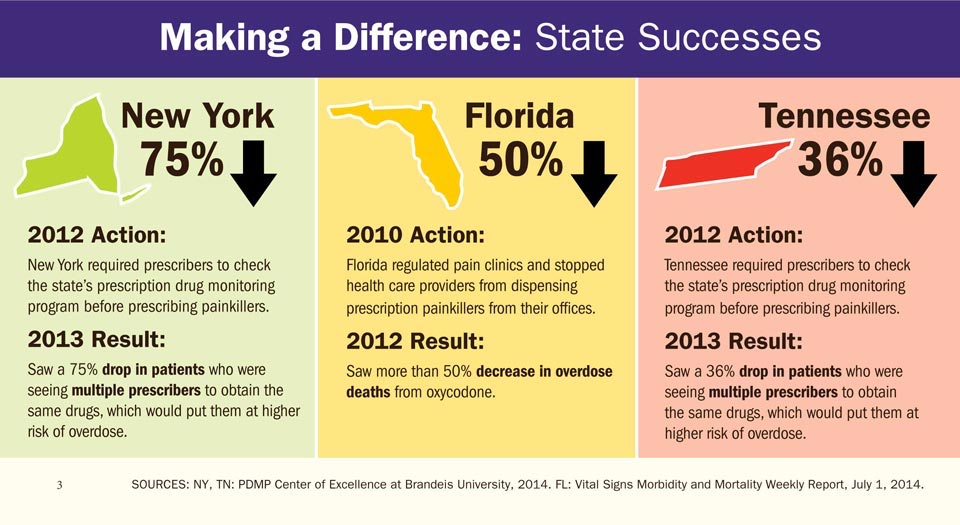

“That’s what the evidence from overseas shows too. New York has brought this in and they showed a huge fall in deaths and harms from prescription medication misuse.

“I think we know for doctors to be able to log on and know that a patient has had three prescriptions of oxycontin in the last week, it gives them ammunition to say, ‘I’m not going to give you any’. Without that it makes it much harder for people.”