A Conversation with Travis Rieder

In 2015, Travis Rieder was hit by a van while he was riding his motorcycle. Unfortunately, this experience crushed his foot and for a long time, doctors weren’t sure whether they’d be able to save it. Over the course of the next five weeks, Travis spent time in three hospitals and had a total of five surgeries as doctors cut, poked and prodded him in an effort to save his foot. Because he was experiencing incredible pain, he was given morphine, fentanyl and hydromorphone through an IV in the hospital. During breaks when he returned home from the hospital, he was also given increasing dosages of oxycodone and gabapentin.

While Travis wasn’t concerned at the time about the amount of medications he was being prescribed, that changed when he visited his orthopaedic surgeon about two months after the accident for a follow-up appointment. It was at that point that his surgeon asked him how much pain medication he was taking.

When Travis nonchalantly told him that he was taking 115mg of oxycodone a day — possibly more — his surgeon turned serious. He said, ‘Travis, that’s a lot of opioids. You need to think about getting off the meds now’.

Because this was the first time anyone had expressed concern about the painkillers he was taking, Travis was stunned. For months he’d been receiving increasingly higher doses and nobody had ever warned him about the risks of opioid dependence.

Travis’ experience with opioid withdrawal

In an effort to get off his pain medications, Travis returned to his prescribing doctor, a plastic surgeon. He asked him how to get off the medication and his doctor suggested they taper his dosage by 25% a week. The consequences were disastrous.

Week 1 – Pain and nausea

The first week of withdrawal, Travis describes was much like a bad case of the flu. Travis explains, “I became nauseated, lost my appetite, I ached everywhere, had increased pain in my rather mangled foot; I developed trouble sleeping due to a general feeling of restlessness. At the time I thought this was all pretty miserable. That’s because I didn’t know what was coming.”

Week 2 – Insomnia and emotional breakdown

By week two, Travis’ symptoms worsened. He began sweating profusely, was covered in goosebumps even in direct sunlight, and started twitching, making sleep all but impossible. He also began crying intermittently for no apparent reason.

When his concerned partner contacted his prescribing doctor, the doctor suggested returning to his previous dose and trying to taper off later. Travis quickly realised that without a better plan to tackle withdrawal in the future, he’d prefer to continue tapering his dose so he’d never have to experience anything similar again. So, he reduced his dosage even more.

Week 3 – Desperation and hopelessness

By the beginning of week three, he had stopped eating, barely slept, and experienced horrible depression. “Several times a day I would get that welling in my chest where you know the tears are coming, but I couldn’t stop them and with them came desperation and hopelessness. I began to believe that I would never recover either from the accident or from the withdrawal,” he said.

Again, his partner was concerned. She contacted his prescribing doctor a second time and this time, he advised her to contact the pain management team Travis saw at the hospital. They were no help. Because Travis was no longer a patient at the hospital, they refused to help him with his symptoms.

So he called his prescribing doctor back and this time, his doctor apologised, explaining he was out of his depth. Travis continued to experience unbearable sleeplessness.

Week 4 – Suicidal thoughts

By week four, Travis felt like he was going to die. Desperately losing hope he and his partner began calling surgeons, pain doctors, general practitioners and rehab facilities.

As desperate as Travis was for help, he quickly learned something very unsettling about the American medical system — virtually no medical practitioners or clinics were trained to help patients wean themselves off opioids

Some of the doctors he spoke to encouraged him to resume taking opioids. Another explained that while they prescribed opioids, they don’t oversee tapering or withdrawal. The rehab facilities Travis called were experienced at transitioning people addicted to opioids to methadone for maintenance treatment, not tapering off opioids completely. Even if they had been able to help, the rehab facilities all had extensive waiting lists.

Travis was broken. After all these fruitless calls, he told his partner he was going to take the lowest opioid dose he could that would eliminate his debilitating symptoms. What happened next could only be described as a miracle. Even though he left his medication untouched, that evening he slept soundly through the night. When he woke up the next day, the worst of his symptoms had abated.

The CDC’s recommended tapering dosage

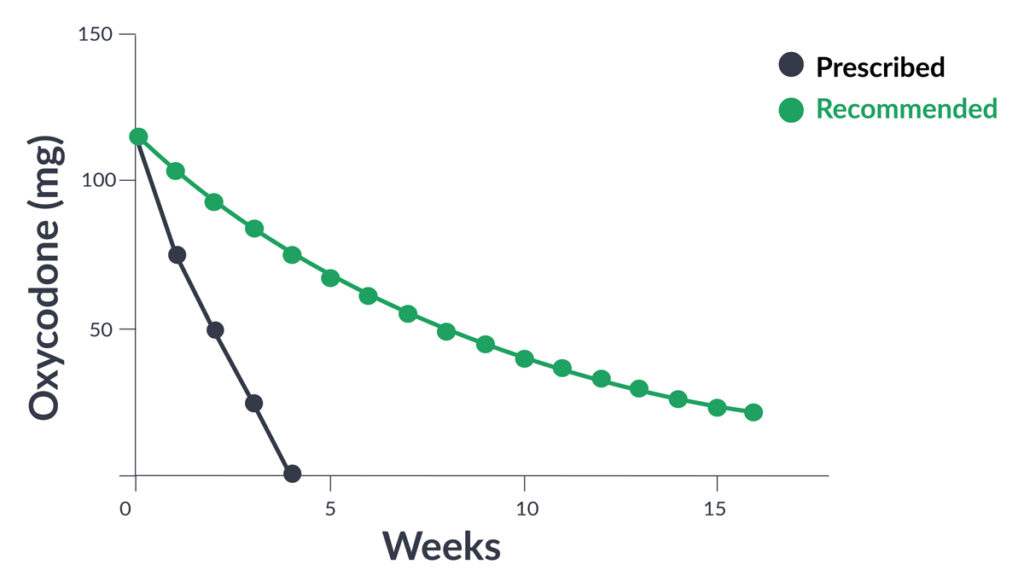

While Travis was lucky enough to free himself from withdrawals without returning to opioids, he learned only later that his method of reducing his intake by 25% was far too aggressive. The Centres for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) actually recommends that opiates be tapered off by 10% per week.

Pictured: The red line shows Travis’ 25% tapering trend. Compare this to the blue line, the CDC‘s recommended 10% tapering trend. Source: Travis Rieder.

CDC also warns that this reduction may be too aggressive for some. For instance, patients who’ve been on opioids for 10 years or longer may struggle even at this rate. In cases like those, it’s best to refer them to a pain specialist who’s more experienced with this phenomenon. Regardless, the CDC goes on to say that patients should be treated individually, and doctors should watch side effects and evaluate.

They also say that even if patients experience withdrawal symptoms, doctors should do their best to keep them comfortable without reversing the taper. Reversing it merely causes patients to associate escaping the discomfort of withdrawal with the drug.

The current state of the opioid crisis

Today Travis is doing much better. He’s the Assistant Director for Education Initiatives, Director of the Master of Bioethics degree program and Research Scholar at the Berman Institute of Bioethics. He’s also a Faculty Affiliate at the Center for Public Health Advocacy within the John Hopkins School of Public Health.

Additionally, he’s involved in a research program concerning ethical and policy issues surrounding the opioid epidemic in America. He’s published an essay in Health Affairs on this subject, frequently writes and talks to the media about it, and has just finished writing a book, In Pain In America, on the role prescription opioids play in American medicine. The book is due out later this year.

When asked about the state of the current opioid crisis, Travis attributes the US epidemic to doctors overprescribing opioids from 1999-2010. During that time frame, prescriptions quadrupled — as did substance use disorder admission rates and deaths from overdoses.

However, Travis doesn’t say that to attribute blame to the medical community. He feels that this was merely the culture at the time, and doctors really didn’t understand the impact of writing those opioid prescriptions.

Between 2010 and 2012, the message did get out and physicians began prescribing opioids less frequently. Interestingly enough, since then, most overdose deaths are now attributed to heroin contaminated with fentanyl.

What appears to be occurring, he says, is that as prescription rates decline, more people are being drawn to the black market to buy drugs. To compound matters, in the United States, only about 1 in 10 opioid patients actually has access to specialised treatment. Not only do a lot of doctors not understand how to taper patients off opiates, but unfortunately, the US medical infrastructure makes it difficult for those patients who actually need to get help from a qualified professional.

Interestingly enough, although the US only has 5% of the world’s population, it has 80% of the world’s opioid use. That said, there’s evidence the rest of the world may be catching up. In Western and Central Europe between 2001 and 2013, opioid prescriptions tripled.

In Australia, opioid prescriptions have also dramatically risen. Between 2009 and 2017 prescriptions rose 40%. Pain specialist Jennifer Stevens believes that Australia is bound to follow the path set by the US. ‘We’re not quite there yet but we are about four or five years behind the situation in the United States’.

The difference between addiction and dependence

To help us better understand the opioid crisis, Travis explains that first, doctors need to understand the difference between addiction and dependence. He explains the distinction by saying that many drugs — like alcohol and SSRIs — cause a physiological reaction once a person’s cut off from them.

As he puts it, “Almost anyone who is exposed to these drugs in high doses for a long enough time gets dependent”. Of course, this means that they’ll experience withdrawal symptoms. However, withdrawal symptoms aren’t evidence of an addiction.

Addiction is characterised by what’s sometimes called the 3C’s — cravings, loss of control and negative consequences. So, people who are addicted to opioids might choose drugs over their family and careers, because they become all-consumed with thoughts of acquiring those drugs, even when the consequences are severe.

There’s a behavioural component that just isn’t present with those dependent on drugs. Travis, for instance, had a house full of pills but didn’t take more than he was prescribed or engage in risky behaviour to try to acquire more. By understanding the difference between these two reactions Travis believes doctors are in a better position to treat their patients.

An answer to the opioid dilemma

According to Travis, one way doctors can help prevent an opioid crisis is to educate themselves more on this subject. Currently, there are a large number of doctors who refuse to prescribe opioids at all. As Travis explains, while on the surface this makes sense, there’s a problem with that philosophy.

For one thing, patients who legitimately need to manage their pain — like Travis — have no way to do so. Unfortunately, this makes them more likely to turn to the black market where they run the risk of even greater problems. When people buy drugs off the black market, they run the risk of purchasing contaminated drugs.

Additionally, they’re dosing themselves, they don’t have a medical professional assessing their wellbeing and they don’t have any help when they choose to taper off.

While Travis is careful not to assign blame — and is fully cognisant of the difficult situation doctors are in — he does believe that physicians need to be comfortable with opioids because as he explains, “they’re the most powerful pain relievers we have.”

He also feels it’s important for doctors to write prescriptions, but believes if doctors are going to do so, they need to understand how to help patients taper off.

He also says a problem occurs when doctors don’t prescribe drugs. While on the surface this may make sense, patients in certain communities may be denied access to drugs that they really need.

In particular, he worries this may be the case in the United States, where evidence shows that white men are most likely to get opioid prescriptions when they’re in pain, whereas women, blacks and Hispanics are more likely to be denied. Unfortunately, there are no easy answers.

The bottom line

Travis’ tale of torment isn’t an uncommon story in the western world. His struggle to find the answers when he needed them most highlighted a dangerously large gap of knowledge when it came to appropriately weaning people off of pain medication.

There is no doubt doctors deserve the utmost respect for the role they play in easing the pain and suffering of their patients. However, there is no such thing as too much education. Travis’ story shows more needs to be done to improve not just how opioids are prescribed, but also how they are tapered and eventually phased out.